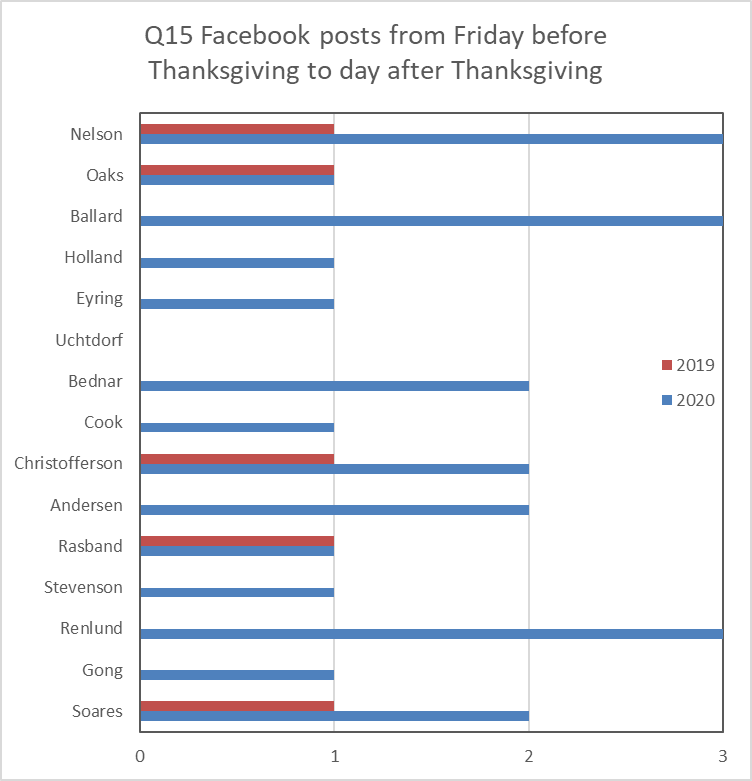

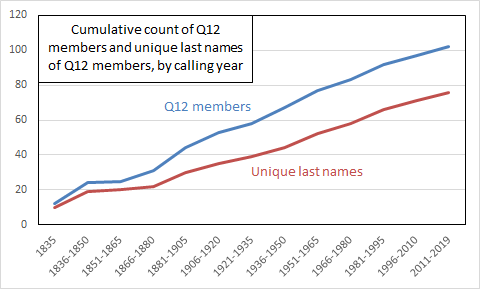

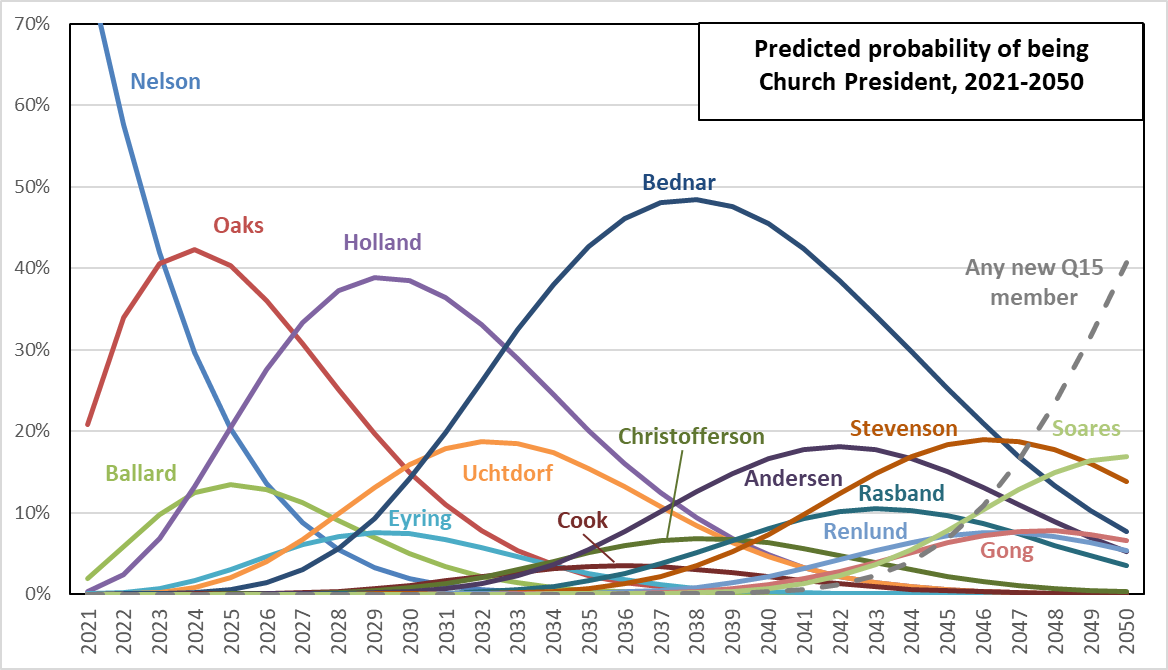

Note: As Jim pointed out in the comments, I mixed up the ordering of the two most junior Q15 members, Elders Gong and Soares. I clearly need to work on my quality control. 🙂 In any case, as it was straightforward to do, I’ve corrected the yearly probabilities graph below. Because it would require more work, I haven’t fixed the remainder of the post with all the parent lifespan-adjusted probabilities. They’re still mostly correct; just ignore the lines for Elders Gong and Soares.

I’ve blogged a number of times about probabilities of Q15 members becoming Church President (see the bottom of this post for links). I’ve always used a pretty similar method to get probabilities: use a single mortality table for all members, simulate their predicted lifespans a bunch of times by drawing random numbers and comparing them to the mortality table, and then check what the implication is in each simulation for who gets to be Church President and for how long.

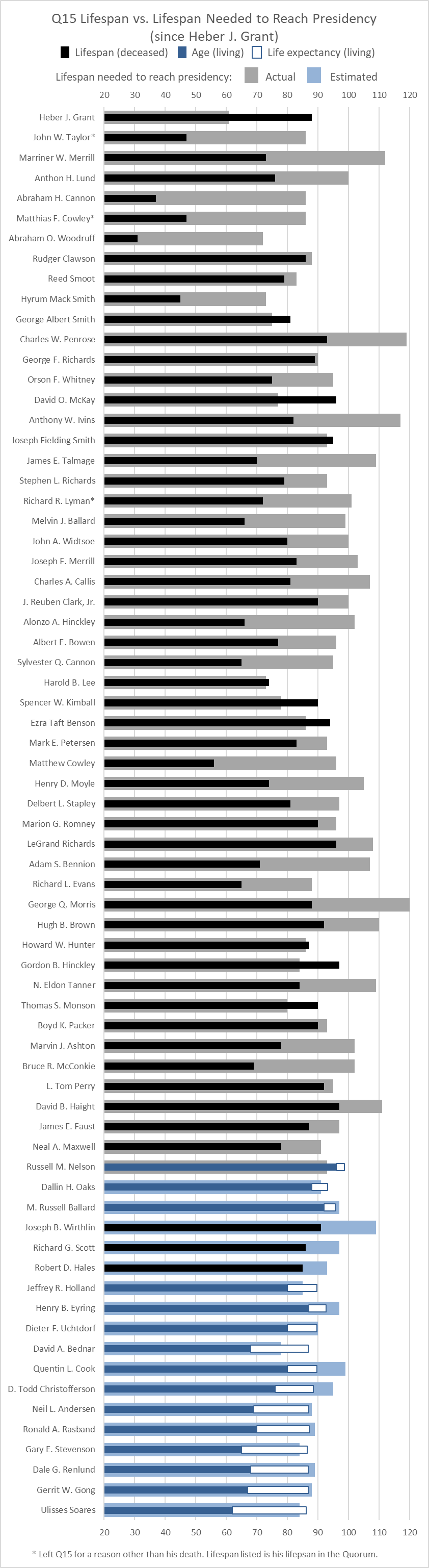

A suggestion that commenters have sometimes made is that I could adjust the expected lifespans of each Q15 member based on how long his parents lived, as surely longevity is at least partly heritable. In this post, I’ll show results from my attempt to make just such an adjustment. I’ve got to warn you, though: this is based on kind of seat-of-the-pants reasoning, and I’ll understand if you don’t buy the assumptions I made. See the Method section below if you want the details.

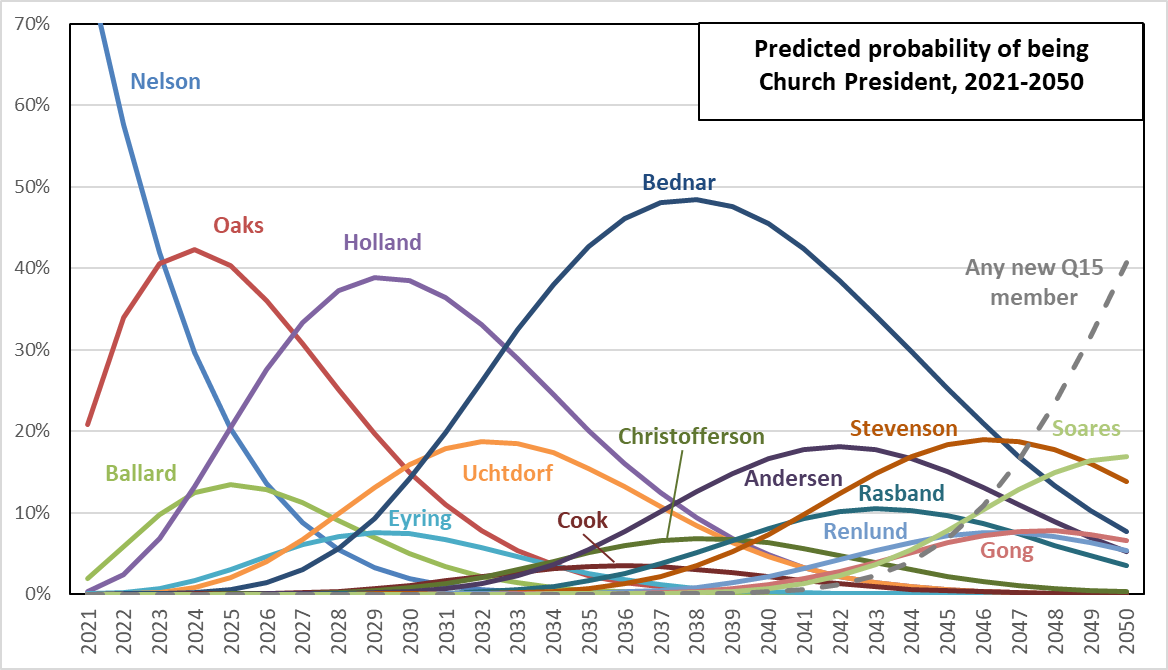

First, though, here’s an up-to-date version of the yearly probability of being President graph that I’ve also shown in a few previous posts. This doesn’t include the adjustments based on parent lifespan that I’ll talk about below. I just take the yearly mortality probabilities for each Q15 member, given their age, from the Society of Actuaries’ RP-2014 table (specifically, white collar males, employee up until age 80, and healthy annuitant after that), and for each member, his probability of being Church President in a year is his probability of surviving to that year times the probability that all the men senior to him have died by that year.

As has been the case since I first looked at this question over a decade ago, it’s President Oaks, Elder Holland, and Elder Bednar who look like the best bets to become Church President. Elders Uchtdorf, Andersen, Stevenson, and Soares might have a shot. The remainder are less likely.

However, keep in mind that the biggest weakness of this analysis is that a mortality table describes the lifespan of large groups of people, and works less well for small groups or individuals. If you’re placing bets on who in the Q15 might become Church President, sure, Elder Bednar is probably a better bet than Elder Cook. But in a tiny sample like 15 men, all kinds of things could happen. Elder Bednar might contract an incurable illness tomorrow. Elder Cook might live to be 110.

President Nelson is a great illustration of how big errors can get. In my first post on the topic, back in 2009, my custom mortality table gave him only a 23% chance of becoming Church President, and an estimated 2.4 years in the position if he did make it. He’s obviously made it to the top spot now, and he’s been in for over three years and seems to be going strong. Of course a 23% chance isn’t really that close to zero, but for sure if I had placed bets in 2009, I wouldn’t have predicted Elder Nelson would ever become President Nelson. So the method can make mistakes, big ones. But of course that doesn’t stop me from using it. I can hardly contain myself, as it’s just so darned entertaining to speculate and guess, and to cloak my guesses in at least a veneer of reasonableness.

Read More