This guest post comes to ZD courtesy of Zatch. Zatch is a lapsed physicist living and working in Washington DC with his wife, son, and another kid on the way. Zatch’s Bloggernacle credentials are that one time he was in this Borderlanders article under his alter ego Zeke: https://forthosewhowonder.com/wp-content/uploads/2006/07/Adolscent-Borderlanders1.pdf

In high school, I was voted “most likely to never buy a car,” and in college my wife studied urban planning. Thus it shouldn’t be a surprise that, after recently attending a cousin’s wedding in the Draper Temple, one of the first things we talked about was how inaccessible the Draper Temple is to anyone without a car. For those who don’t know, the Draper Temple is far up on the hillside, 3+ miles (5+ km) from and 500+ feet (155+ meters) of elevation above the freeway. Unless you are into hiking or mountain biking (things we actually saw people doing on the way in), it is not easy to get there without a car.

This is actually a conversation my spouse and I have a lot. Between work, school, missions, etc. the two of us have lived in at least 8 temple districts across the US. Ignoring Utah for a moment (a place where they literally built cities around the temple), nearly every temple near which we’ve lived has been located not in the city it is named for, but rather one of the city’s wealthy suburbs:

- Tucson -> Catalina Foothills

- Indianapolis -> Carmel

- Detroit -> Bloomfield Hills

- Atlanta -> Sandy Springs

- Oakland -> Oakland, but up a steep hill from downtown and still in a wealthy neighborhood

- Washington D.C. -> Kensington, MD

My personal inclination is that the entire temple-going experience favors those with money. If it were up to me, clothing rental would be free, childcare would be provided, and we’d be opening more cafeterias instead of shutting them down (especially since, as I’ve claimed without evidence, many temples are in wealthy residential areas without places to eat). But that is a rant for another post.* Today I want to focus on one specific aspect of temple attendance: getting there.

Assumptions

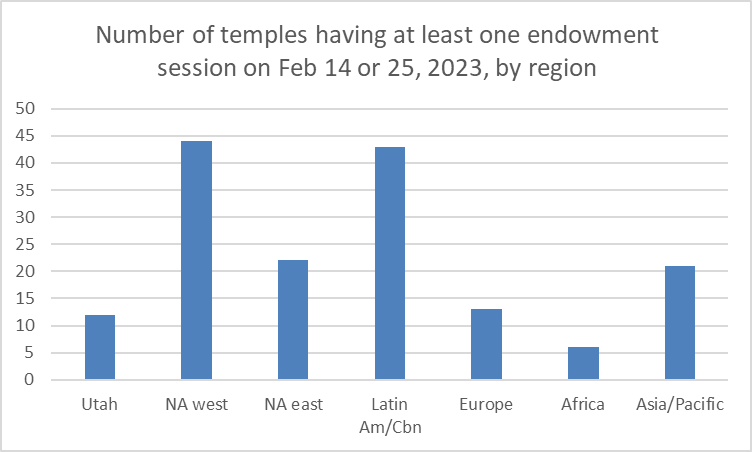

I started from the most recent list of temples on the church website. From there, I filtered out any that have not yet had a location announced, but I did include several that are currently under construction but where the location has been announced. I cut out any temples that were named for geographic features rather than cities (e.g. Gila Valley, Mount Timpanogos). This left me with a list of 212 temples, which I grouped into regions using the same bins that Ziff used in his most recent temple-related post.

As my measure of “ease-of-access,” I used Google Maps to estimate how long it takes to travel from the city center (as defined by Google) to the temple, traveling by 1) car, 2) public transit, and 3) foot.** I set the departure time to 7am on a Saturday to avoid issues from current local traffic. The choice to use city center as a point of origin is easily the weakest point of my analysis, but I still think it’s a reasonable assumption for a couple of reasons:

- For members who live in the specified city, you could assume (and this is clearly an assumption) that they are randomly scattered throughout the city such that on average they live near the city center. Some will live in the northwest, some in the southeast, but hopefully those differences all cancel each other out when you include enough people.

- For members who do not live in the specified city and who must arrive by bus, train, or other public transit, I think it’s plausible that they would be dropped off at a terminal somewhere near the city center and then continue to the temple from there.

I thought about using the nearest (non-temple adjacent) meetinghouse as a point of origin instead of the Google-appointed city center, but that would have at least doubled the effort so I didn’t do it. This might give us a better indicator of the average member location than what I did, so please let me know if anyone gives it a try.

Results

The first question I decided to answer is “How many temples are accessible by public transit?”

I noticed that some of the Utah temples (e.g. Ogden) were showing no public transit option even though I know for a fact that’s not true. Given that the Ogden temple is two blocks from what I would consider the city center, I’m guessing Google has a hidden “why on earth would you take a bus for this?” feature. To compensate, I added a 15-minute walking distance filter; that is, if you can walk from the Google-declared city center to the temple in 15 minutes or less, it counts as having a public transit option. The following table shows the number of temples in each region, and the percentage of temples inaccessible via public transit.

| Region |

# of temples in region |

# with no public transit |

% with no public transit |

| Africa |

8 |

6 |

75.00% |

| Asia & Pacific |

32 |

10 |

31.25% |

| Europe |

14 |

1 |

7.14% |

| Latin America & Caribbean |

53 |

25 |

47.17% |

| Eastern North America |

27 |

9 |

33.33% |

| Western North America |

54 |

17 |

31.48% |

| Utah |

24 |

7 |

29.17% |

| Worldwide |

212 |

75 |

35.38% |

Read More