In a recent discussion in a Facebook group, I guessed that one way the Church might have improved recently in its treatment of women is in GAs using more gender-neutral language in talks. My memory is that President Hinckley, for example, when he quoted scriptures talking about men, would sometimes explicitly point out that it included women as well. But I’ve never actually studied the question systematically. Until now.

To answer the question of whether GAs have actually used more gender-neutral language recently than they used to, I used Mark Davies’s wonderful Corpus of General Conference talks. Since this was a rough study (I’m all about quick and approximate!) I simply looked up the frequency of use of gender-specific personal pronouns: she, he, her, hers, him, and his. Then I calculated two percentages that compare the female words to the male words. First, I calculated the usage of she as a percentage of the usage of he. Second, I calculated the usage of her and hers (combined) as a percentage of usage of him and his (combined). Note that I did this combining because of the ambiguity of her (object or possessive determiner) and of his (possessive determiner or possessive pronoun).

To compare these results against more general historical trends, I looked up the same set of words and calculated the same percentages for two other sources. The first was Google Books and the second was Mark Davies’s Corpus of Historical American English (COHA), which includes books, magazines, and newspapers.

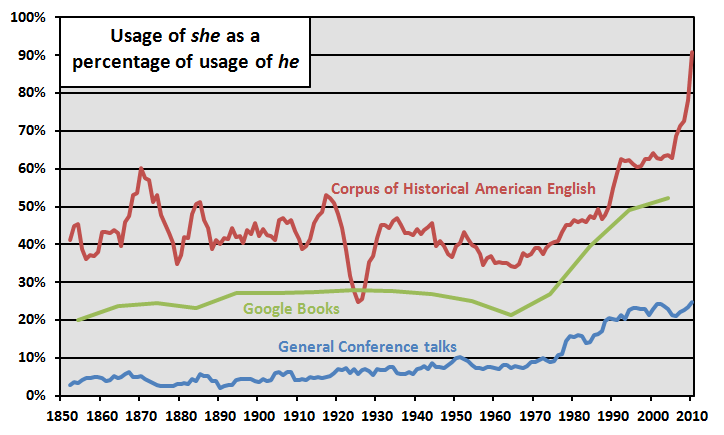

This graph shows the she/he percentage since 1851 (as far back as the Conference corpus goes). The lines for COHA and General Conference are five-year moving averages. The Google Books data are only available by decade, which is why its line has fewer zigs and zags.

The most striking thing in the graph is probably that the General Conference line is so much lower than the others. From 1850 to 1950, the she/he percentage was always less than 10% in Conference talks. In Google Books, it was about 20 to 30%; in COHA, it was typically 40 to 50%. All three series show increases that coincide fairly well with the rise of second wave feminism, starting in the 1960s and 1970s. The increase for Conference is the smallest in absolute terms–to only about 25%–but is the largest in relative terms, as it represents more than a doubling from its previous level.

This is probably obvious, but an important thing to note is that these percentages can be thought of as ratios: the ratio of how often she is used to how often he is used. This means that a value of 100% says that the ratio is 1:1, or perfectly balanced. Also, although this never happened in the data, it’s entirely possible for the ratios to exceed 100%, if she is used more often than he.

The overall difference between Conference and the general corpora isn’t surprising, of course. We have male leaders and, until fairly recently, only male speakers in Conference, and scriptures written almost exclusively by and about men. To say nothing of a male God. With all those patriarchal structures and texts, it would be surprising if Conference didn’t have lower usage of she. I am encouraged at the recent increase, though. What I was expecting to find was that it would lag the increases in the worldly data by decades. And it might lag them by a few years: it wasn’t until 1980 or so that the Conference fraction moved decisively above its historical average. But it’s surprisingly close in time, I think.

Comparing Google Books and COHA, I have no idea why the books are lower. Maybe because COHA includes periodicals and book publishers are by nature more conservative (since they’re publishing stuff that’s supposed to last more than a day or a week)? One thing I can say is that it appears at the end of the series that the increase in the she/he percentage was more dramatic in COHA than in Google Books. I don’t think this is evidence of a real difference, though, because it could be entirely driven by the difference in the granularity of the data.

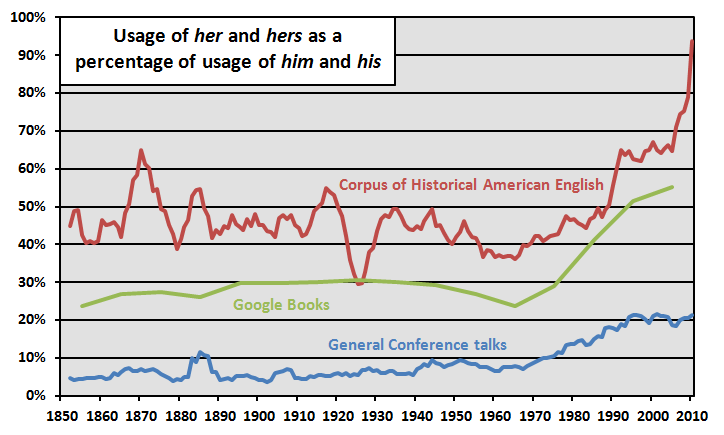

This graph shows the (her+hers)/(him+his) percentage since 1851. As in the previous graph, the lines for COHA and General Conference are five-year moving averages and the Google Books data are only available by decade.

I know you think I made a mistake, that this is just a copy of the previous graph with a different title. But it’s actually a completely different graph using totally different data. Really. I went back and checked. And if you look closely, like in one of those “find ten differences between these two pictures” games in the Friend, you’ll see there are some clear differences. For example, in this graph, the Google Books line spends several decades right at 30%; in the previous graph it is more like 27%. In this graph, the lowest dip of the COHA line barely reaches down to cross the Google Books line in the late 1920s; in the previous graph, it crosses more clearly. In this graph, the last few years of Conference percentages have been right around 20%; in the previous graph, the corresponding values are all above 20%.

The similarity in the graphs doesn’t give us anything new to talk about, but it is nice to see as a check on the reliability of the results. You would expect to see she, her, and hers varying together: when one goes up, they all go up. You would expect the same for he, him, and his. So it’s good to see that the she/he and (her+hers)/(him+his) percentages track each other pretty closely across time for all three data sources.

One last thing to say is that of course simply counting individual words is a very crude way to get at the use of gender-neutral language. I chose this approach because it was easier than looking at individual uses of the words, where I could track down how often she was actually being used to clarify that scriptures can apply to women too. But of course usage of the individual words is also affected by other things like changes in how often women are referred to in stories, and how often women are addressed directly. These reasons for increasing usage of female pronouns in Conference are all probably correlated, though, and I think they are all probably generally positive. It may be that General Authorities still tell women they’re wonderful too often, but on the bright side, at least they see the need to talk to and about women. The results of these word counts suggests that it wasn’t that long ago that they didn’t.

“What I was expecting to find was that it would lag the increases in the worldly data by decades. And it might lag them by a few years: it wasn’t until 1980 or so that the Conference fraction moved decisively above its historical average. But it’s surprisingly close in time, I think.”

It looks like the general upward trend lags by about 8-10 years, which isn’t too bad. But sadly, we top out at about 25%, which is roughly equivalent to the lowest percentage ever in either COHA or Google books. It likely is partly due to the ratio of male speakers to female, but I think our history of patriarchy plays the greatest role. After all, if you’re going to tell a church history story, it’s more likely to be about men because that’s what we recorded. And if you’re quoting church leaders or talking about them, 9 out of 10 times, they’re men as well. But it seems like we could make more of an effort to talk about women, especially now that so much work is being done on women’s history. 25% is somewhat disappointingly low for 2010.

One interesting thought that came to mind for me, and that may account Partly for the differential is that our history has truly been a HIStory, without much HERstory interwoven. The major figures of Mormon history (which would easily be recounted and repeated often in Gen. Con.) are almost exclusively male.

[I note that this only partly accounts for the disparity. Obviously we do have entrenched patterns of male-centeredness, and based on these graphs, more so than more broad-ranging views of American culture. Further, with an all-male priesthood, there have been fewer and more difficult avenues for women to inject themselves into the history of the church]

My $0.02 to add, anyway…

A more telling calculation would exclude the use of “he” and “him” in scriptures, and “He” and Him” as references to deity. But that would require context-based analysis.

Does this include the RS and YW sessions? That wouldn’t make a huge difference, but there are a lot more stories with female protagonists told there.

It would also be interesting to look at the increase in the bracketed feminine pronoun as in: “While other institutions such as church and school can assist parents to “train up a child in the way he [or she] should go” (Proverbs 22:6), this responsibility ultimately rests on the parents.”

That’s a great question, Thokozile. I searched for a couple of phrases from 2009 General RS and YW meetings, and I was able to find them in the corpus, so I guess they are included. Since the women’s meetings started in the 1980s, it’s possible that they could account for all the increase in usage of female pronouns. That would be depressing!

And you have a good suggestion for another way to search. I decided not to look at that level of detail because I don’t think the way that scriptural language gets gender-neutralized is standard (different speakers have done it different ways) and I was too lazy to try to track them all down. 🙂

What is the ratio in the standard works? My guess is it is somewhere in the pre-1980 range from conference. If a speaker just gets up and quotes scripture, then he is certainly quoting many more he/his/him.

Ziff,

After seeing such an impressive analysis I don’t think anyone is going to accuse you of being lazy. Thanks for putting this together. It seems encouraging and sobering at the same time.

Lately I have often heard that General Conference speakers try and use gender neutral language. I’m trying to think where…maybe on fMh or Mormon Stories Sunday School. Anyway, I’m wondering if anyone knows if general authorities have ever said in talks, manuals, policies, etc., that we should all be trying to use more gender-neutral language. That would be a welcome development if it has indeed happened.

Great question, el oso. I searched using lds.org. Unfortunately, it lumps she and her together and he and him together, so I can only get one estimate of the percentage. The value is 12%, which, interestingly enough, is higher than the historical average for Conference. So Conference speakers, at least by this analysis, have historically been even more sexist in their language than the scriptures (although with the more recent increase, this is no longer true).

Mike C, thanks! I don’t know that I’ve ever seen anyone say explicitly that we should, but of course that doesn’t mean someone hasn’t. I agree that it would be great if someone had!

Years ago I did a study of gendered language in LDS scripture, and the percentage of female language was on the order of 3% … with the Doctrine & Covenants being the worst out of the Bk of M and PofGP.