In my last post, I looked at how often children in Utah, Idaho, and Arizona are named after the current Church President. I thought it also might be interesting to look at how often children are named after people in the Book of Mormon. One advantage of looking at Book of Mormon names is that it doesn’t require me to limit myself to states with lots of Mormons. If you’re naming your child Nephi, you’re probably Mormon, regardless of where you live. The downside, of course, is that this rules out names that are not unique to the Book of Mormon. For example, someone naming their child Benjamin may be thinking of the Book of Mormon king, but there are many other Benjamins out there that their choice was more likely inspired by.

Because using a Book of Mormon name is a clear marker of Mormonness, there’s even good reason to have a hypothesis beforehand about what the data will look like. In The Angel and the Beehive, Armand Mauss talks about the Church’s shift between the 1960s and 1990s from leaning toward assimilation with the broader world, toward more retrenchment. I think it would make sense to expect that Mormons would use more distinctly Mormon names during a period of retrenchment, when drawing bright lines between the Church and the world is an important practice, than during a period of assimilation. Therefore, I expected to see increasing usage of Book of Mormon names between the 1960s and 1990s.

I got data from the same sources as I did for my last post: the Social Security Administration (SSA) name database for counts of how often names are used by state and year from 1960 to 2014, and CDC Vital Statistics reports for counts of total births by state and year for the same time period. Here is an alphabetical list of the Book of Mormon names I checked:

Abinadi, Abish, Helaman, Jarom, Lehi, Limhi, Mahonri, Mormon, Moroni, Mosiah, Nephi, Omni, Sariah, Teancum, Zeniff

I looked at the girls’ names first: Abish and Sariah. Unfortunately, Abish only shows up in three of the years (1999, 2000, and 2003). The SSA database doesn’t report counts of less than five (for either a state or the entire country), so it’s likely that the name was used in other years, but just fewer than five times. For Sariah, I ran into a different problem. I thought it was a uniquely Book of Mormon name, but while the SSA data shows elevated levels of usage in Utah, Idaho, and Arizona, the name also appears in lots of other states. Overall, Utah, Idaho, and Arizona account for only 11% of uses of the name. I wonder if it isn’t being used by people not referring to the Book of Mormon as an alternative spelling of Saria or another takeoff on Sara(h). In any case, given that the name doesn’t appear to be an indicator of Mormonness, I put it in the non-unique bin with names like Benjamin.

For three of the boys’ names, I found no hits at all: Limhi, Mormon, and Zeniff. Because of the reporting threshold of five, this doesn’t mean these names are never used, but if they are, it’s clearly very rare.

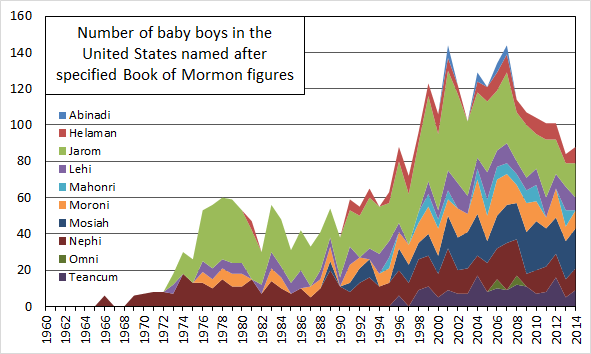

The remainder of my analysis looks at just the remaining ten names. Here’s a graph showing how often they are used in the full US data.

To me, the big surprise here is Jarom. I would never have guessed that it would be used most among the list of names I started with. I included it kind of as an afterthought, since he’s such a minor character.

To me, the big surprise here is Jarom. I would never have guessed that it would be used most among the list of names I started with. I included it kind of as an afterthought, since he’s such a minor character.

Another notable point here is how very small the counts are. The maximum is about 140 in the entire United States for an entire year. Clearly naming your kids after Book of Mormon figures is not a very common practice even for Mormons.

As far as my assimilation-vs.-retrenchment-based hypothesis, it looks like there’s an increase from near zero in the 1960s to the higher levels in the 1990s (and even higher levels since), so that’s good. Of course, I can hear you pointing out loudly that these counts don’t take into account the different total numbers of babies born by year in the US, not to mention the fact that the Church was growing during these years, so there were different numbers of babies born to LDS families too. And while you’re bringing up issues, you probably also noticed that when I said at the beginning of this post that naming your child Nephi is probably something only done by Mormons, I was carefully sidestepping the fact that there are lots of churches other than the LDS Church that are traced to Joseph Smith’s church and read the Book of Mormon and might name their kids Nephi just as happily as LDS members do.

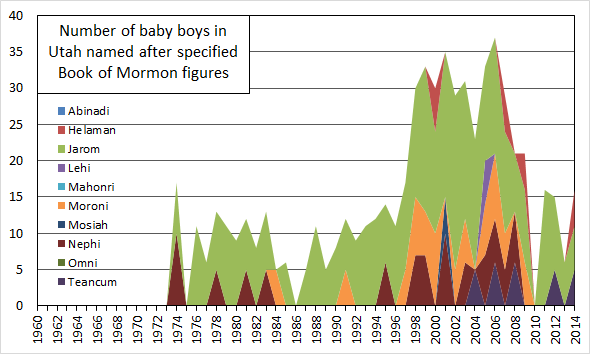

I’ll go after this last issue first. One way to correct for it is to just look at the data for Utah. This reduces the influence of the Community of Christ and other more Midwest-centered churches, although it doesn’t remove fundamentalist sects in Utah. Anyway, for what it’s worth, here’s the Utah data. The increase from near zero in the 1960s to small nonzero values later is still there. And Jarom is still the surprising champ. But in looking at the trend over time, there’s still the problem of different numbers of total births and LDS births.

The increase from near zero in the 1960s to small nonzero values later is still there. And Jarom is still the surprising champ. But in looking at the trend over time, there’s still the problem of different numbers of total births and LDS births.

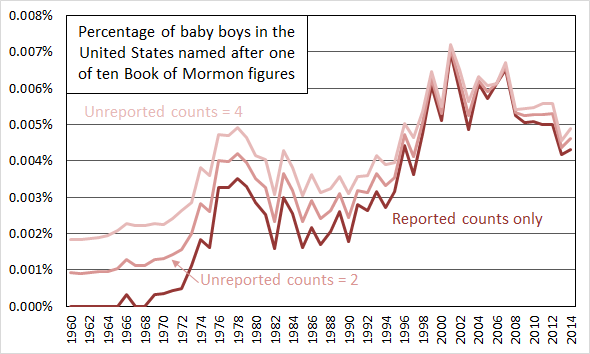

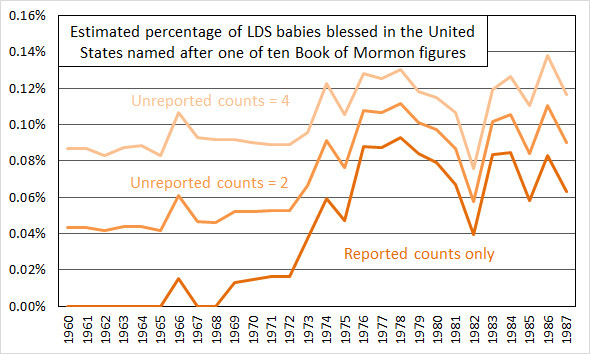

In this next graph, I go back to counts for the entire US, and divide by the total number of boys born in the year to get percentages. To make the graph easier to look at, I just use the sum of the counts for all ten names, rather than showing the names separately. Also, I calculate the total count three different ways. Recall that the reporting threshold for the SSA data is five, so no counts of less than five are reported. The three different ways I get the total vary in how I treat names that have a reported count of zero. The first way (shown with the darkest line) is to just take the counts with no adjustment, and count zero as zero. The second way (medium-dark line) is to assume that any count of zero takes on the median of its possible values: two (possible values when not reported are zero to four). The final way (lightest line) is to assume that any count of zero takes on the maximum possible value of four. The lines show the range of possible actual percentages if we had the full data with no minimum reporting threshold. I suspect that the truth is generally closer to the darkest line than the lightest, as a scenario where none of the names are used at all seems more plausible to me than one where several of the names are used just the right number of times to fall right below the reporting threshold.

Consistent with the counts, the percentages are really small. The upward trend is still present, even now that I’ve adjusted for total births, and even if we look at the upper bound line, where all zero counts are assumed to actually have values of four.

Consistent with the counts, the percentages are really small. The upward trend is still present, even now that I’ve adjusted for total births, and even if we look at the upper bound line, where all zero counts are assumed to actually have values of four.

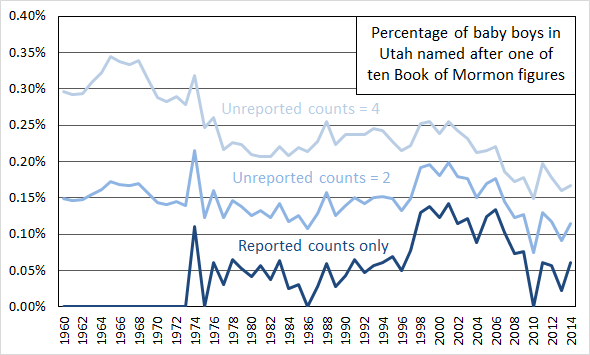

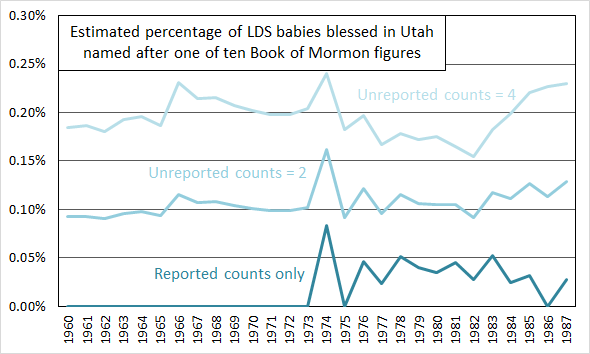

This graph still doesn’t adjust for the number of births to LDS families. I’ll go back to the Utah data and make a similar graph, which is a step toward solving the problem. The percentage of births in Utah that are to LDS families has probably fallen across time as Utah has become less overwhelmingly LDS. This means that where in the national data, this change I haven’t accounted for (increasing numbers of births to LDS families) runs in the same direction as my assimilation-vs.-retrenchment-based hypothesis, in the Utah data, the change I haven’t accounted for runs in the opposite direction from my assimilation-vs.-retrenchment-based hypothesis. Therefore, in the national data, the increase in births to LDS families as a percentage of all births is an alternative explanation for the increase in percentage of boys given one of the ten Book of Mormon names I’m looking at. But if there’s a similar pattern in the state data, it can’t be an alternative explanation because the effect is running in the opposite direction, so all else equal, it would push the percentage of boys given one of the Book of Mormon names down.

The upward trend is maybe sort of still here, depending on how much we trust the bottom line versus the middle and top ones. There’s a lot of uncertainty, though. Compare how close together the lines are for the national data in the previous graph, particularly in more recent years, to how far apart they are in this graph. In years up to 1972, the SSA data for Utah has no data for any of the ten names, which could mean as few as zero actual uses, or as many as 40 (four per name). The pattern in the national data can give us a clue about the likelihood of these different scenarios. In the national data, other than one year with six boys named Nephi, all ten names have reported counts of zero every year from 1960 to 1968, which means that the only way the Utah line could be near the top line is if there were consistently four uses of each name per year in Utah, but no uses in any other states (or else the names would show up in the national data). This all seems quite unlikely to me, so I think the truth is probably much closer to the bottom line than to the top one.

The upward trend is maybe sort of still here, depending on how much we trust the bottom line versus the middle and top ones. There’s a lot of uncertainty, though. Compare how close together the lines are for the national data in the previous graph, particularly in more recent years, to how far apart they are in this graph. In years up to 1972, the SSA data for Utah has no data for any of the ten names, which could mean as few as zero actual uses, or as many as 40 (four per name). The pattern in the national data can give us a clue about the likelihood of these different scenarios. In the national data, other than one year with six boys named Nephi, all ten names have reported counts of zero every year from 1960 to 1968, which means that the only way the Utah line could be near the top line is if there were consistently four uses of each name per year in Utah, but no uses in any other states (or else the names would show up in the national data). This all seems quite unlikely to me, so I think the truth is probably much closer to the bottom line than to the top one.

I made one last attempt at adjustment by getting counts of births to LDS families directly so I could divide the counts of uses of Book of Mormon names by them. I used the number of babies blessed (or children of record born, which I’m treating as the same statistic), which used to be reported in General Conference up until the late 1980s. Unfortunately, it wasn’t reported by state or country. To get approximate breakdowns for Utah and the US, I use Tim Heaton’s entry “Vital Statistics” in the Encyclopedia of Mormonism. His Figure 3 shows the distribution of Church members by region every ten years from 1930 to 1990. The region categories I use are Utah, West US (minus Utah), and Eastern US + Canada. For this last category, I just split it in half, and took the US total as Utah + West + (1/2)*[Eastern US + Canada]. This is all very rough approximation anyway, as Figure 3 is a bar chart, so I have to guess the percentages by eyeball. Finally, for years in between those shown in the graph, I just do a linear interpolation between the values in the graph. For example, if a percentage is 40% in 1960 and 35% in 1970, then I take the percentage as 39.5% in 1961, 39% in 1962, and so forth. Note that of course this whole process is assuming that LDS families have the same birth rate regardless of where they live, which is probably not true.

Here is the resulting graph for the US. I’ve divided the counts of babies named using one of the ten Book of Mormon names by the estimated number of births to LDS families in the US. As with the previous two graphs, I calculate the counts three ways: once using just the reported counts, a second time assuming that unreported counts are actually two, and a third time assuming that unreported counts are actually four.

There is still probably an upward trend from the 1960s to later decades. Note that the graph only goes through 1987, as that’s the last year that the General Conference statistical report included anything like a count of births.

There is still probably an upward trend from the 1960s to later decades. Note that the graph only goes through 1987, as that’s the last year that the General Conference statistical report included anything like a count of births.

Here’s the corresponding graph for Utah.

As with the previous graph for Utah, the trend is maybe up from the 1960s to later decades, but it’s not a long way from being flat.

As with the previous graph for Utah, the trend is maybe up from the 1960s to later decades, but it’s not a long way from being flat.

In the end, I don’t think the evidence for my assimilation-vs.-retrenchment-based hypothesis is very strong at all. Even if the trends over time were dramatically increasing, the total counts of parents naming their kids after Book of Mormon figures remains so small that I don’t think this is a very good indicator of retrenchment. A good measure of retrenchment would show an effect for a lot of members, not for a tiny percentage. And all that being said, the trends over time aren’t dramatically increasing; they maybe kind of sort of increased from near zero in the 1960s to something greater than zero since then, but that’s about it.

I’m sorry that there isn’t much interesting here in the end. I’m posting this anyway because I found putting the data together to be a fun exercise, and I hope you enjoyed my description of it too.

Interesting! I’m unsurprised by Jarom since I know a couple (I think the name sounds similar to Jared, Jason, other normal/non-Mormon specific names) but surprised by some of the others. I do think we also tend to have a lot of Ammons. I’ve noticed that Book of Mormon names seem much more common in Polynesian/Hispanic ethnic groups than among white church members. It might be intriguing to trace Hinckley and Maxwell (both genders) in the past twenty years too.

One note: the name “Mahonri” does not actually appear in the Book of Mormon, though tradition has it as part of a BoM character’s name. (The other part of the name, “Moriancumer”, appears in Ether 2:13.)

One change you might want to make is the addition of the Spanish spelling “Nefi.” I’ve noticed (though my evidence might just be anecdotal) that Spanish-speaking members seem more willing to give their kids Book of Mormon names; I knew a Chilean “Moroni” on my mission, for instance.

My name is Abish.

acw, good point about Jarom. It makes sense that it sounds perhaps not too far away from other more common names, so it doesn’t sound as odd in non-Mormons’ ears as say Nephi does.

Anon #1, good point. I was thinking of saying as much in the post, but then it totally slipped my mind when I got around to writing it up.

MH, good thought. Perhaps I’ll look at that if I update the analyses later.

Anon #2, that’s so cool! Now we know that your name is extremely uncommon (at least if you live in the US). Thanks for sharing that!