Geoff Nelson at Rational Faiths wrote an interesting post a few weeks ago where he looked at how often General Conference speakers say “I know” versus “I believe.” Hooray for more data analysis in the Bloggernacle! Anyway, he found that usage of “I know” has been increasing relative to “I believe” since the early 20th century. I found this kind of surprising, because I would have guessed that the rise of Correlation would be associated with any change over time, but the pattern he found is different than what you would expect to see if that were the case. So I thought I’d look at the data a little bit myself.

As Geoff did, I got data from the Corpus of General Conference Talks. Because I’m mostly just interested in this more recent increase, I only looked at 1900 forward (sorry, Ardis!). Geoff looked farther back in his post.

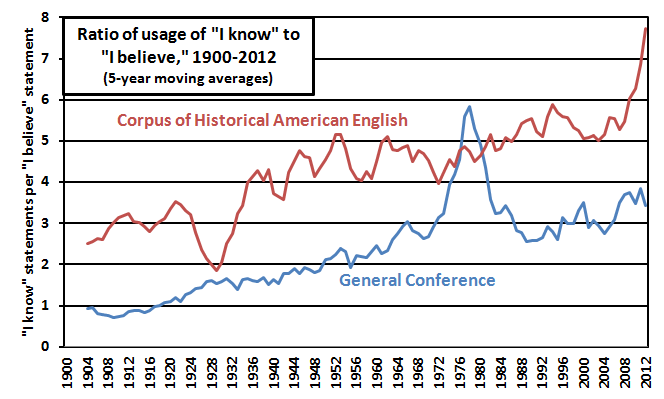

One question I had was whether this trend of saying “I know” more often than “I believe” was different from changes over time in American English more generally. If you read ZD closely (and I don’t blame you if you don’t!) you might remember that a few years ago, I blogged about usage of “obey” and “reason” (as a verb) and found that changes over time in Conference usage were not consistent with changes over time in more general usage. Like with that post, for this post I used the Corpus of Historical American English (COHA) to compare against the General Conference data1.

For “I know” versus “I believe,” it looks like the Conference trend isn’t even keeping up with the more general trend out in the world. Note that to make the data easier to look at in one graph, I took the ratio of “I know” usage to “I believe” usage for each year (making the result comparable to Geoff’s second graph). Also, because the year-to-year variations are so great, I am showing 5-year moving averages.

The Conference ratio has a spike around 1980, and the COHA ratio has a dip around 1930, but other than that, they’re both generally increasing, but with the Conference ratio typically trailing the COHA ratio by a pretty wide margin. (Note that the uptick in the COHA data in the last few years is probably not real, but rather a result of my failure to adjust adequately when I added contemporary data. See footnote 1.) This suggests that the change over time is probably not evidence of a change in the Church, but is rather likely reflecting the change in American English more generally. If anything, the consistent lower ratio in Conference seems likely to be a more interesting issue to study.

The Conference ratio has a spike around 1980, and the COHA ratio has a dip around 1930, but other than that, they’re both generally increasing, but with the Conference ratio typically trailing the COHA ratio by a pretty wide margin. (Note that the uptick in the COHA data in the last few years is probably not real, but rather a result of my failure to adjust adequately when I added contemporary data. See footnote 1.) This suggests that the change over time is probably not evidence of a change in the Church, but is rather likely reflecting the change in American English more generally. If anything, the consistent lower ratio in Conference seems likely to be a more interesting issue to study.

Thinking about the question a little more, I wonder if looking at “I know” and “I believe” isn’t failing to capture how Conference speakers are actually expressing their certainty. Consider three possible ways of testifying of Christ:

- “I believe that Jesus is the Christ.”

- “I know that Jesus is the Christ.”

- “Jesus is the Christ.”

Certainly I think nobody would say #1 in Conference today. But I don’t think they really say anything like #2 either. My impression (and I haven’t checked) is that Conference speakers express certainty by just going to #3 and making a statement without any reference to themselves. I think this kind of makes sense, too, why they would do it. Clearly #1 is open to the possibility that other people believe differently. But even #2, by starting with “I know” suggests that others might not know, or might even disagree. Statement #3 neatly skips past these issues by leaving the speaker out of it and just making the statement as the way things are, without any unintentional reference to other people disagreeing or not knowing. Unfortunately, #3 would be a much more difficult pattern of speech to study, because there’s no single phrase to search for.

So that’s a big caveat. The Conference trend is likely not capturing a real change in the Church, and it may be missing the most emphatic way speakers express certainty. But since I already got the data, I thought it might be more fun to look at it in a little more detail. Please take the following with an even larger grain of salt than usual.

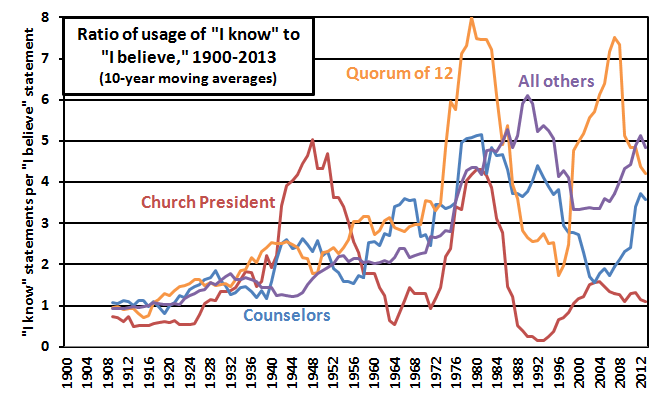

I went back and noted the name of the speaker who gave each talk, matched those up with their calling (and in some cases release) dates, and looked at the trend across time for speakers holding different positions at the time they gave their talks. Because there’s less data when it’s sliced into these different groups, I moved to showing 10-year moving averages.

I can’t see a whole lot here. Of course the Church President line goes up and down as the presidency is handed from one man to the next. It’s no surprise that they might be different in what phrases they use or don’t use. It looks like the Quorum of the Twelve have had two big spikes. One is around 1980, suggesting that they drove the spike in the overall ratio in the first graph. But their more recent spike, in the 2000s, didn’t push the overall ratio up, because the other groups were flatter during that time period. I’m not sure if that means anything. In fact, it seems likely to me that this whole graph is just noise, but I’d love to hear any theories you have about it.

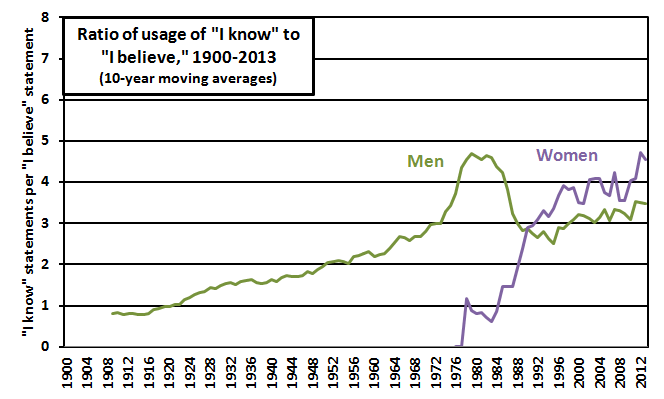

Next I split the data into women and men. Women first show up in the Welfare Sessions (I think) in the 1970s.

Wow! I wasn’t really expecting to find anything here, but it does look like since the 1980s, women might have had a greater tendency than men to say “I know” as opposed to “I believe.” I should offer an additional caveat: the data for women are of course pretty sparse, even though it appears that RS and YW sessions are included in the data.

If I might spin a quick hypothesis, it has long been my impression that some women who have served in auxiliary presidencies at the general level have tried to make names for themselves by being more orthodox than orthodox. Julie Beck, for example, always struck me this way. If this were true, it would be consistent with women in such positions wanting to say they “know” even more often than General Authorities do.

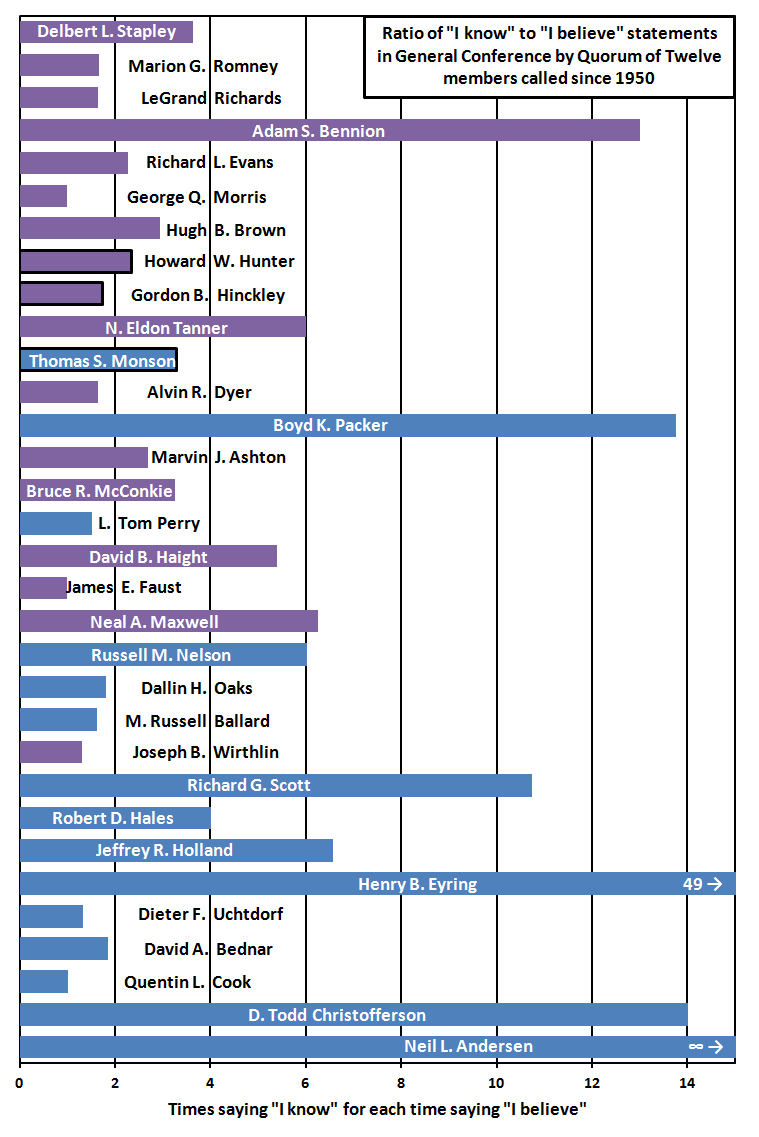

Finally, I looked at ratios for some individuals. To prevent the graph from becoming overwhelming, I included only members of the Quorum of 15 who were called in 1950 or after. I figure these are the speakers we have the most data (talks) from, so they are the ones whose results we can have some confidence in, as reflecting their real preferences for one phrasing over the other.

The men in the graph are ordered by calling date. Former members have purple bars; living men have blue bars. Church presidents have a black border around their bars.

Bruce R. McConkie’s ratio is only about 3:1. He was a pretty emphatic, sure-of-himself speaker. This probably highlights the weakness of this measure in capturing certainty. Boyd K. Packer at #4 is no surprise, but the top three are all surprises to me. Henry B. Eyring is at 49:1? And Neil L. Andersen has yet to say “I believe” in a Conference talk.

Bruce R. McConkie’s ratio is only about 3:1. He was a pretty emphatic, sure-of-himself speaker. This probably highlights the weakness of this measure in capturing certainty. Boyd K. Packer at #4 is no surprise, but the top three are all surprises to me. Henry B. Eyring is at 49:1? And Neil L. Andersen has yet to say “I believe” in a Conference talk.

I have the data by individual for all talks since 1900 (so it will be incomplete for anyone who gave talks before then). Let me know in the comments if there are other people you would like to see ratios for. Also, please feel free to suggest your theories for any of the results I’ve found.

_________________________

1. Since this corpus (COHA) only goes up to 2009, I supplemented it with data from the Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA) for 2010 – 2012. Because they use different source material, COHA and COCA do not agree in their results in the years that they overlap (1990 – 2009). To correct for this, I calculated the average ratio of COCA hits to COHA hits for the phrases across the matching years, and then divided the COCA data for 2010 – 2012 by this ratio.

I wonder what the context of the “I believe” statements in General Conference are. I’ll have to check that out.

Perhaps you could look into the usage of “I testify.” I think it is more frequent than “I believe,” is almost always applicable in the same context as “I know”, yet is more nuanced. If nothing else, it will have a different pattern than the COHA.

Hey, I’m becoming more and immersed in 20th century history. I know it. I believe it. No, I know it. Hmm.

Ziff, great job doing a real analysis. At some point we should team up to do some large statistical study on Mormony stuff.

Last Lemming, good idea! I’ll have to look at that!

Ardis, ha! I thought I saw from your FB posts that you were doing quite a bit of work in the 20th century now.

Geoff, we totally should! It’s so fun to have more people doing data stuff on the bloggernacle! (And sorry–I didn’t mean at all to imply that your analysis wasn’t real. I just wanted to follow up on it with even more analysis! 🙂 )

I haven’t mastered the CGCT yet, so I am just playing around with it and can’t produce the kind of detail that you do. But I looked at “I testify” and “I know” in conjunction with “Jesus” and “Christ” and found an interesting pattern. The following represent approximate ratios of “know” to “testify” over time:

1900-1959: 20

1960-1979: 6

1980-1989: 1.8

1990-1999: 1.4

2000-2009: 1.0

2010-2013: 0.4

Hopefully, you can come up with something a bit more coherent.

Last Lemming, that’s great! I didn’t even look at who/what speakers were testifying of with “I believe” or “I know.” It’s interesting that you found the same general pattern where “I know” came to dominate “I testify” over time, just like it has come to dominate “I believe.”

Oh, sorry! Now I see I got it exactly backwards. You’re saying that “I testify” was increasing relative to “I know.” That’s exactly what I found too, when I looked at the GC corpus without limiting to references to Christ (to make the results comparable to my previous results).

Also, I looked in the COHA to see if there was a comparable trend in more general American English usage, but the phrase “I testify” is virtually never used in the sources it draws from.

So Ziff, would it be a correct interpretation of your last figure to conclude that Elder Anderson knows infinitely more than any other apostles, past and present? Although according to his stats, at least he wouldn’t believe it, or anything else, for that matter.

Exactly, Mike! I think Elder Andersen listened to Douglas Callister’s “Knowing That We Know” talk one time too many. He not only knows. He knows that he knows. He doesn’t just believe that he does.

There doesn’t seem to be any obvious relationship between political position and believe/know.

I would have expected there to be more Knows the more conservative the person.

Can you tell me if there is or not?