A few weeks ago in my elders’ quorum, we had the lesson from the George Albert Smith manual on the Word of Wisdom. As often happens with lessons on this topic, a couple of people raised their hands and talked about how the Word of Wisdom is the perfect health code, that it tells us exactly what we must do to be the healthiest we possibly can. Along similar lines, in response to some provocateur asking why we don’t drink a little wine since some research suggests it might be good for us (no, the provocateur was not me :D), people also commented that if any “science” (their tone suggested the quotation marks) suggested something different than the Word of Wisdom, then the science was sure to be proven wrong sooner or later.

The manual is more conservative. While it says that we’ll be physically blessed for following the Word of Wisdom, it doesn’t say that the Word of Wisdom is necessarily the perfect health code. I think this is actually a strength of the commandment: it’s reasonable, but it’s not too reasonable.

The benefits of having reasonable commandments are pretty clear. I think the major benefit is that the more reasonable a commandment is, the more likely people are to comply with it. If Church leaders tell us to get out of debt, for example, the reasons they’re saying we should are obvious. Of course we typically have competing interests (getting more education, buying a house, etc.) that might make actual compliance difficult, but I suspect people typically don’t argue with the suggestion itself. Or to take a more exaggerated example, if Church leaders told us to be sure to eat regularly, compliance would likely be extremely high.

But there’s a cost to making commandments too reasonable. If we can reach the same conclusions about what we should do by reasoning things out ourselves as we can by listening to Church leaders, why would we listen to them? Why not just cut out the middle men and do the reasoning ourselves? I think this is why commandments have to be at least somewhat unreasonable, or in other words, at least a little bit arbitrary. If commandments are too reasonable, we may comply with them at a high level, but we will be less likely to attribute our compliance to a desire to follow the commandments. Instead, we will simply attribute our behavior to doing what makes sense, particularly if commandments got as extreme as my “eat regularly” example.

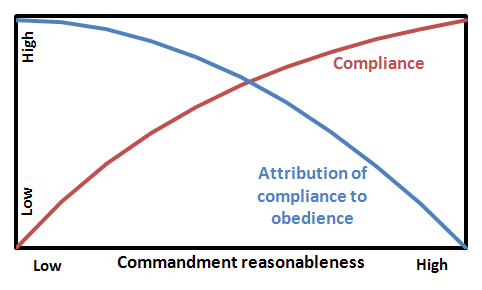

Here’s a graph to illustrate:

As commandments get more reasonable, compliance goes up, but our attribution of our compliance to obedience to commandments goes down. (Note that I’m not trying to say anything with the particular shapes of the curves. I could have them completely wrong. I just think the one is increasing and the other decreasing.)

As commandments get more reasonable, compliance goes up, but our attribution of our compliance to obedience to commandments goes down. (Note that I’m not trying to say anything with the particular shapes of the curves. I could have them completely wrong. I just think the one is increasing and the other decreasing.)

As both compliance and attribution of compliance to obedience are goals of commandment writers, this suggests that there is an optimal level of (un)reasonableness for commandments. They should be reasonable, but not too reasonable. I think the Word of Wisdom is a good example of this balance. The abstaining from alcohol and tobacco seems very reasonable. The abstaining from coffee and tea seems pretty arbitrary, especially considering that the Word of Wisdom (particularly in the form it’s asked in the temple recommend interview) includes such a short list of behaviors, and how many other unhealthy things aren’t explicitly mentioned. On the whole, it’s reasonable enough to get fairly high compliance, but also unreasonable enough that if someone complies, it’s fairly easy for her to attribute her compliance to a desire to follow the commandment rather than just a desire to be healthy.

Having said all this, I must concede that I might be overgeneralizing from a single example. Much of what Jesus taught seems extraordinarily unreasonable. For instance:

Love your enemies, bless them that curse you, do good to them that hate you, and pray for them which despitefully use you, and persecute you

This is very difficult to comply with, but if you do, you probably wouldn’t question why you were doing it.

So I’ll leave this to you to answer. Are most commandments in the Church in the optimally (un)reasonable spot I’ve argued the Word of Wisdom falls? Or are most of them in the extremely unreasonable end with “love your enemies”? Or maybe do a lot of them fall toward the end where they’re too reasonable? Or perhaps does this categorization of commandments by reasonableness not even make sense?

I like this! I think there’s a nice mix of the reasonable and unreasonable in our canon. I mostly think religion is one of those things that transcends reason–or, at least the reason of our puny mortal minds–but having some commandments that have logical underpinnings is handy for those of us who are fond of the “but, why?” line of questioning. I don’t mind living with the “my thoughts are higher than thy thoughts” answer some of the time, but it’s nice to be able to understand the reasons why on many things.

The prohibition on tea and coffee are always interesting to me. Caffeine in all but small amounts triggers migraines for me, so in a word-of-wisdomless world, I still wouldn’t drink coffee. But tea, especially green and white, is one of those arbitrary obedience things. I like having some of those, though, because it’s a chance to practice self-restraint, which is an important ability.

I’m not sure I’d categorize “love your enemies” as unreasonable. Unexpected, yes. But I guess I’d define “unreasonable” in this context as commandments in which adherence brings no obvious, directly-correlated benefit (aside from the aforementioned self-discipline). Learning to love those who hate you is a step towards having the pure love of charity. Although, maybe acquiring charity is one of those things that isn’t, strictly, “reasonable” (which, of course, does not indicate that it is not desirable, or laudable or needful for any of those good things)–we know that at the last day “it will be well with those” who have it, but that’s sort of a fuzzy benefit. I’ll have to think more on that one.

Thought-provoking as always, Ziff. Okay, I can agree with a discussion focused on the optimal degree of reasonableness in fashioning a commandment. But the general problem is utility maximization: what we are maximizing is human well-being or utility. I think the two variables in the function are compliance and individual benefit, which are themselves in some way related to reasonableness (a fuzzy concept that needs to be tightened up). I’m not sure attribution really contributes to utility.

The problem with reasonableness is that a very difficult commandment may be deemed unreasonable from the point of view of compliance (it asks too much) but very reasonable from the point of view of benefit (it offers the best outcomes). So instead of reasonableness, let’s focus on “difficulty.” Assume that a commandment with high difficulty, d, offers maximal individual benefit but also produces lower compliance. Then your function becomes:

U[C(d), B(d)]

with C compliance decreasing in d and B benefit increasing in d. That will produce the tradeoff you are after in overall human utility as a function of difficulty and give an optimal degree of difficulty that is not a corner solution.

Interestingly, at least for the Word of Wisdom God seems to give greater weight to compliance, which is “adapted to the capacity of the weak and the weakest of all saints” (D&C 89:3). I find that encouraging.

Really interesting post. As a psychologist, I think it would be fascinating to delve into what people consider to be “reasonable”. As we know, common sense often leads people to solutions that would actually benefit their lives, but often common sense goes counter to what happens in the real world. Furthermore, what is considered to be “reasonable” changes across contexts and throughout time. I would imagine that 50 or so years ago, many LDS members considered it reasonable that the wife should obey the husband and should defer to his decisions. Those ideas seem less reasonable today.

This is fascinating, Ziff, and makes me think of debates from the functionalist school in anthropology of religion. For example, Bronislaw Malinowski argued that, broadly speaking, the purpose of religion is to soothe people’s anxieties about life’s uncontrollable, unknowable elements. Radcliffe-Brown countered that religions serve to create as many anxieties as they assuage, but that by creating anxieties (about sin, proper performance of ceremonies or rituals, etc.) religions help to solidify and unify communities. So maybe the tension created by unreasonable commandments – the anxiety inherent in doing something that isn’t easy to justify rationally – is itself the source of bonding for the community.

Great post.

This is an excellent angle on the malum prohibitum versus malum in se. Most sins in the church occur because we prohibit the action not because the action is innately wrong.

God marks a spot on the curves where he thinks the weakest should be. Through personal revelation and maturity, what was once unreasonable becomes reasonable.

Wow! Great comments! I think y’all thought about this question more carefully than I did in writing the post.

Laura:

I’m not sure I’d categorize “love your enemies” as unreasonable. Unexpected, yes. But I guess I’d define “unreasonable” in this context as commandments in which adherence brings no obvious, directly-correlated benefit (aside from the aforementioned self-discipline).

That’s a great point. There’s clearly benefit to learning to love your enemies. I guess I was thinking more that this is difficult, and difficulty and unreasonableness are (probably?) correlated. But then I was actually trying to keep the two separate (at least in my head) so you’re doubly right that this is a poor example if I’m going to talk about unreasonable or arbitrary commandments. Maybe the two earring rule is a better example.

Dave

That’s a good reframing. I did a bad job of making this explicit (i.e., I didn’t do it at all), but I was thinking of self-perception theory when I talked about our attributing our compliance to a desire to be obedient as a good thing. Self-perception theory says that we make attributions about our own behavior and draw conclusions about ourselves. These attributions are sometimes mistaken, for example, we can ignore other reasons that we might behave in particular ways and attribute our behavior to our own personality. Anyway, what I was getting at is that two goals of commandments are to (1) have people comply with them, and (2) have people come to see themselves as commandment followers. For the second goal, people attributing their compliance to a desire to follow commandments is a good thing.

I hope this makes some sense, or at least clarifies the post a little. Thanks for pushing me to explain my thinking more clearly.

Beatrice

That’s a great point about possible changes over time. I was actually thinking the question of making commandments optimally unreasonable is at least a little related to Armand Mauss’s theory of optimal tension, where the Church has changed over time to maintain a good level of tension with the surrounding culture. Similarly, I think the Church changes over time in order to keep commandments from becoming too reasonable or too unreasonable. For example, the reduction in the size of the garments from ankle and wrist length to sleeve and knee length seems like a clear attempt to avoid making the commandment to wear them too unreasonable.

Galdralag

So maybe the tension created by unreasonable commandments – the anxiety inherent in doing something that isn’t easy to justify rationally – is itself the source of bonding for the community.

Yes! Exactly! This relates to the self-perception theory stuff I mentioned in responding to Dave, that I should have put into the original post. I think psychologists call it dissonance reduction where people who go through difficult experiences to get into a group are then more loyal to the group. (The same should hold for people who go through difficult experiences as members of the group.) So I think you’re spot on, exactly right.

gibbyg

That’s a great point about the difference between things that are wrong in themselves and things that are simply prohibited. I guess in talking about optimally unreasonable commandments, I was kind of assuming that most wrongs are just prohibited wrongs, and that the lines defining what’s prohibited needn’t be drawn precisely where they are.

My brain froze on some of your post, as well as this part of a comment “the malum prohibitum versus malum in se.”

So I’m not sure I understand what you (or the other commenters) were trying to say, exactly.

I do not believe the Word of Wisdom is, or was ever meant to be, a commandment. I believe it is a wise suggestion. There are many different ways people can live that are healthy and they are relative to their particular situation and inklings. For instance I have very healthy (non-Mormon) friends who are vegans, but drink wine and smoke the occasional joint.

I believe Mormonism attracts task-oriented people who need rules. And those types of people use the rules to compete with others in their race to the Celestial Kingdom, missing the point altogether.

This is a bit of a threadjack (sorry, Ziff) but if I’ve said it once, I’ve said it a million times: we are asked if we keep the Word of Wisdom in our recommend interview, but we are NOT asked if we love our neighbors. So we have a bunch of recommend holders running around who are jerks, but don’t smoke.

A few weeks ago, a new member of our ward, a young physician’s assistant in a pediatrics clinic, spoke by way of introduction and made this statement “our buildings should smell like smoke!” He was saying that we should welcome those with word of wisdom (and other) problems. I agree.

I haven’t been blogging much recently, or reading too many blogs, but I have addressed commandments, though from a differnt angle:

http://ethesis.blogspot.com/2012/11/understanding-commandments-rough-draft.html

Annegb — malum/se means bad in and of itself (maum = bad). malum/pro means bad because it is prohibited.

Lots of things are illegal because they are bad in and of themselves. But driving on the wrong side of the road is bad is bad because it is prohibited, not because there is anything special about which side of the road is driven on.

Hope that helps.