The discussion of “raising the bar” in Steve Evans’s Friday Firestorm #24 last month at BCC got me to thinking about what the possible effects of this more stringent missionary screening policy might be.

The screening process that includes interviews with a missionary candidate’s Bishop or Branch President can result in two types of errors. A candidate can be approved to serve a full-time mission when he or she should not have been, or a candidate can be kept home when in fact he or she was qualified to serve. If the goal of the screening process is thought of as a medical test diagnosing “shouldn’t serve syndrome,” the first kind of error would be a failure to diagnose a true case (a miss), and the second kind would be diagnosing someone who isn’t a case (a false alarm).

So what does raising the bar mean for these two types of errors?

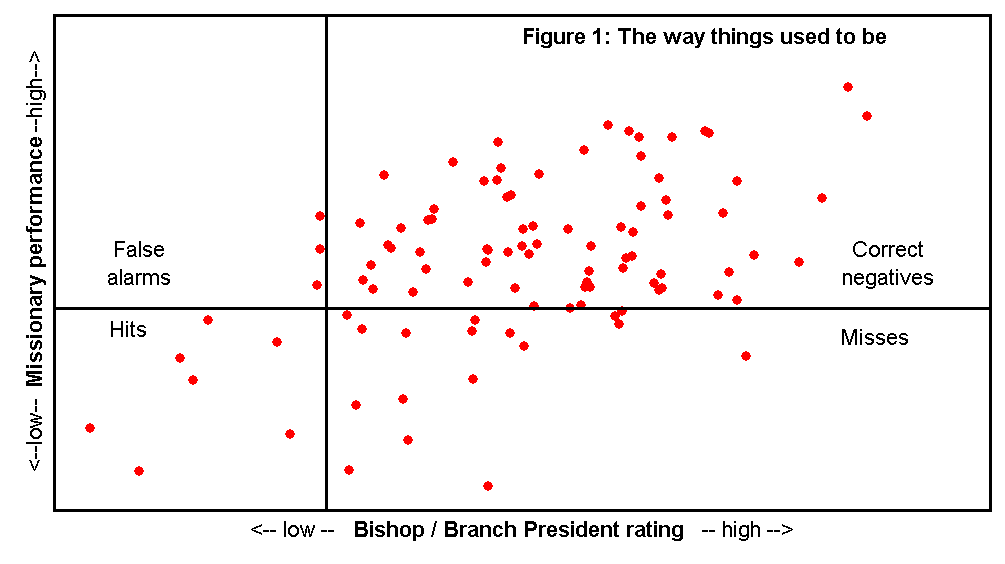

Consider Figure 1.

In this figure, I’ve made up data for 100 hypothetical missionary candidates. Each has a score on Bishop or Branch president rating (on the X-axis, running from low on the left to high on the right) as well as on actual performance as a missionary (on the Y-axis, running from low at the bottom to high at the top). The vertical line running through the plot divides the candidates qualified by their Bishop or Branch President rating from those not qualified. The similar horizontal line divides the candidates actually qualified by their performance from those actually not qualified.

These two lines also divide the figure into four quadrants. The upper left quadrant has the false alarms, the candidates who are above the line in terms of actual performance, but below (to the left of) the line by Bishop or Branch President’s rating. The lower right quadrant has the misses, the, the candidates who are below the line in terms of actual performance, but above (to the right of) the line by Bishop or Branch President’s rating. The two types of correct decisions are also labeled. The upper right quadrant has the correct negatives, candidates who are qualified by both criteria, and the lower right quadrant has the hits, candidates who are below the line by both criteria.

You may notice that the cutoff line for actual performance is more stringent than is the cutoff line for the Bishop or Branch President rating. Twenty five candidates fall below the performance cutoff, but only 10 fall below the rating cutoff. The result of this difference is that there are far more misses (18) than false alarms (3). Although the numbers are of course made up, if I understand Elder Ballard correctly, this is how things used to be, with too many unqualified candidates being sent on missions.

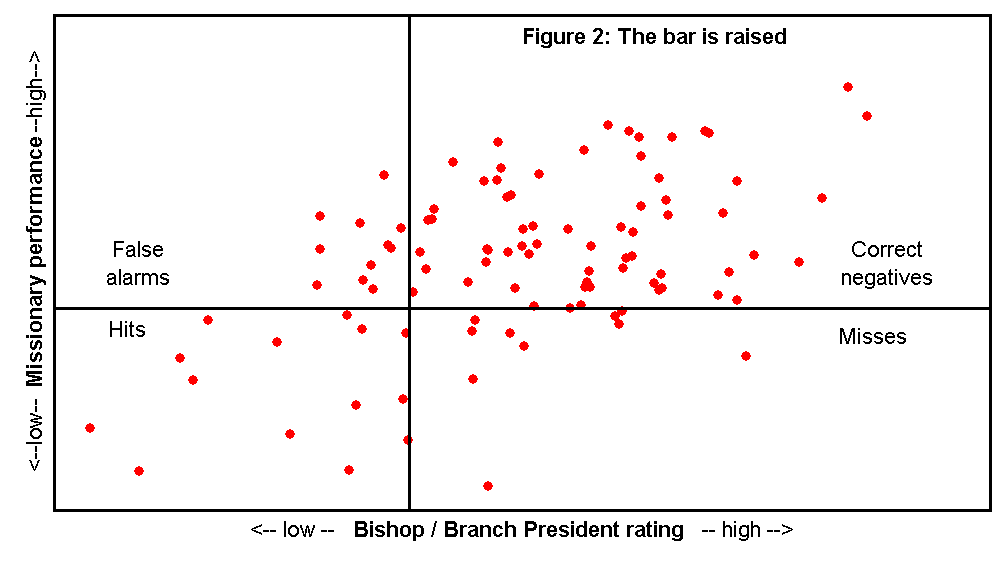

So what happens when the bar is raised, when the screening cutoff is moved up to more closely match the performance cutoff? This situation is shown in Figure 2.

Now there are 25 missionaries falling below each cutoff, and the number of misses equals the number of false alarms (11 each). While this perfect symmetry of errors is unlikely to be the case in real life, the result is clear. The effect of raising the bar is to decrease misses while increasing false alarms.

In setting a cutoff for a screening test like the one for being allowed to serve a full-time mission, a major consideration is how harmful the two types of errors–misses and false alarms–are compared to each other. For example, in medicine, a preliminary screening test for a disease might use a very low cutoff because false alarms are much less costly than are misses. If you tell someone they don’t have a disease and you’re wrong (a miss), they could get really sick, die, or sue you. If you tell someone they do have a disease and you’re wrong (a false alarm), it’s much less costly. Sure, the person will be irritated, but all they’ll likely have to suffer through is a more expensive and more accurate test, which will likely tell them correctly that they don’t have the disease.

By contrast, William Blackstone’s famous preference for allowing ten guilty people go free rather than punish one innocent person implies that false alarms (false convictions) are ten times as bad as misses (erroneous acquittals). Although the ten to one ratio of importance may not be exactly how they’re treated, I think criminal law still has the preference that misses are better than false alarms.

By “raising the bar,” I think the Church is making a decision similar to the one in the medical screening example, figuring that misses are more costly than false alarms. In other words, it’s better to incorrectly keep a qualified missionary home than it is to incorrectly send an unqualified missionary out.

To think about how this conclusion might have been reached, I’ve listed some possible costs of the two kinds of errors.

Possible costs of misses (unqualified missionaries sent out):

- They don’t do missionary work. They waste the resources of the Church missionary structure.

- They make the Church look bad. They behave badly in front of members, investigators, and the general public.

- They change the norms for the missionaries around them, making it appear more acceptable to not work very hard.

- They suck up the time of their companions, preventing them from doing missionary work.

- They suck up the time of mission leaders, who spend time trying to get them to work harder or more effectively.

Possible costs of false alarms (qualified missionaries kept home):

- Fewer people are converted. Even poor missionaries may help convert some people.

- Candidates kept home may feel mistreated by the Church, may become bitter, and may leave Church activity.

- Missionary service helps prepare future leaders. Candidates kept home may be less effective as leaders, or less likely to serve as leaders. The fewer missionaries who serve, the smaller the pool of returned missionaries to draw on later for leadership positions.

- The norm of having all young men serve a mission may erode, making it more difficult to get qualified missionary candidates to serve.

It appears to me that the conclusion that misses are more costly than false alarms is a reasonable one. At the very least, a false alarm’s costs are pretty much borne by a single person, while a miss has the potential to harm many people around the “missed” candidate.

But what do you think? Which possible costs are the most damaging? What are other possible costs of the two types of errors? Have I misstated any of those that I have listed?

I’ve seen lately several people who weren’t approved for missionary service, based on medical conditions, get called as part-time service missionaries. I wonder if that lessens the blow a bit.

I see a possible correlation to scouting, in that this generation of scouts no longer faces the same “Eagle Scout or bust” machinations that my generation (mid-80s) went through. Leaders today are more willing to let it side if you didn’t want to do it (they will still bust their humps to get that kid an Eagle, but they won’t go to extravagant lengths anymore).

Similar to missions — the standards for missions are higher, meaning that if a youth is going to go, he has to prepare much, much harder (this aspect is different from scouting, where the requirements haven’t changed), but there is definitely less of an attitude of “we’ll move heaven and earth to get a boy on a mission, so that he’ll grow up in the process”. There is a bit less of an emphasis of getting a boy ready to serve if he’s just not interested.

(Sister missionaries are different. While the Church doesn’t give much program support to preparing girls to go on missions, I don’t think the bar has effectively changed for sisters. A 21-year-old woman who wants to go is as ready today as she would have been 15 years ago, I think.)

But I detect a trend of “you don’t want to do X, we won’t make you do X” cropping in programs like scouting, missions, and seminary.

I agree that the cost of “misses” is greater than the cost of “false alarms”.

Although I also think you are exaggerating the problem of false alarms. Let’s say someone is on the line, but is qualified, and the bishop says he or she is not. Firstly, it’s hard for me to imagine that this happens that often. Even with the bar being raised, I think there will still be many more misses than false alarms (although I guess that depends on where you feel the horizontal line should be). In any case, what would happen to such a person? Most likely the family would get involved and talk to the Bishop and work out a plan to get the kid on a mission. Perhaps the Stake President would get involved. It wouldn’t just be a “No” and that’s it. Maybe I’m just naive, but I think that most of the “false alarms” would eventually end up going anyway.

Re: 2

You don’t think it has changed for sisters? Dang. I have been in singles wards since my mission (going on 7 years now) so I don’t really know. In my mission we had at least 6 sisters while I was out who should have stayed at home due to mental health issues but went home early and finished with service missions. I sincerely hope that some of the “raise the bar” effect has included sisters as well. I definitely think that the cost of “misses” are greater than “false alarms,” having experienced many comps who just were not up to missionary work, despite some of their good intentions.

I just wrote a long comment on the impact of false alarms, but my computer decided to have internet issues and it got eaten. It’s pretty late, so now I’m just going to summarize.

I think false alarms are much worse than many people think, especially as they’re related to medical issues. It’s hard to prepare for missionary service your whole life, be excited about it, and then be told that your service isn’t wanted. I think the impact is even worse with the “raising the bar,” since boys are now told they have to be more righteous and work harder to prepare. Putting that much effort into preparing for something that you’ll never be able to accomplish through no fault of your own can be devastating.

I had a friend in college who struggled with going to church because he always felt like people were judging him because he came back to school after his freshman year instead of going on a mission. What many of them didn’t know is that he’d wanted to go but had been “excused” for medical reasons. The sad thing is, many people were judging him, without ever knowing him or asking him about it, thinking that he simply chose not to go. Like I said, I think this will only be worse as the bar is raised — boys will be told their service isn’t wanted, and those around them will judge them for not going. Many people aren’t going to bother to find out that there was a medical reason their service was refused — they will just assume these boys were not righteous enough to go.

So in my opinion, false alarms (at least among those who really want to go on missions) are much worse than misses. But then again, I’ve never seen any direct negative impact from misses, and I have from false alarms (and not only the above example). (That isn’t to say there isn’t a direct negative impact from misses, just that I haven’t ever experienced it.)

Chelle – The bar has been raised for both men and women, but I think from a practical purpose, it has had a less impact on women than on men.

This is just a gut feeling, based on observation. I see sisters going on missions with roughly the same frequency as they were in the late 90s. The raised bar is probably weeding out some sisters who can’t cut it for medical reasons, but I don’t think it’s catching as many sisters who are morally unfit or unprepared as it is elders. That is partly due to the cultural expectations of missionary service for sisters vs. elders.

Ziff, all of this is based on assumptions regarding the purpose of raising the bar. I’m not sure that “reducing misses” is really what it’s all about. My theory is that it’s motivated largely by two things, neither of which have to do with actually producing better missionaries per se. 1. Putting a cork on a (Utah) culture of young men that believed you could sleep around as much as you wanted beforehand and still go. 2. Relieving the headache of Mission Presidents whose time was absorbed dealing with young men and women who simply weren’t mentally/emotionally mature enough to take on the tasks of a mission.

I’ve no doubt the Brethren are acutely aware that this would mean and has meant many fewer missionaries and the subsequent challenges faced by those who don’t go. But I think the tradeoff of this decision got them a lot more than just a few less misses.

Queuno, that’s an interesting point about candidates who are turned down getting alternate assignments. I agree with you that that seems like a good way to reduce some of the costs of false alarms (assuming some are being turned down who should have been approved).

Mike L., I think I see what you’re saying, but I think there will be always be some candidates who are turned down, some of them in error. If the candidates scoring 51 (on some arbitrary scale) are sent on missions, but those who score 50 have to scratch and claw to go, then those who score 49 will be kept home in spite of their extra efforts. Or if the 49ers are sent, the 48ers will be kept home. Someone will always fall just below the cutoff, even taking into account their best string pulling and meeting with the bishop.

Chelle and Queuno, regarding the question of Sisters versus Elders, I tend to think that raising the bar should have had less effect on Sisters because they are a more self-selected group to begin with, while Elders are a broader cross-section of the 19-ish year old males in the Church. But that’s theoretical. I think that conclusion would be more likely to be wrong the more Sisters self-select to try to serve a mission for reasons other than feeling a strong desire to preach the gospel (e.g., to enhance marriage prospects (sorry! 🙂 )).

Vada, thanks for telling about your friend who was unfairly judged for not serving. Several people shared similar experiences on Steve’s BCC thread, and that’s what got me to thinking about the cost of false alarms in the first place. You’re certainly right that I didn’t even consider the issue of candidates turned down for reasons other than worthiness issues.

Eric, I think you may have misunderstood me. Certainly your #2 is exactly the same thing as avoiding misses. Misses are missionaries sent who shouldn’t have been sent who impose costs on those around them. And although I focused on a kind of vague “missionary performance” criterion here, I’m thinking of the whole set of reasons why a missionary should or shouldn’t serve, so I think the worthiness issues you raise in #1 are misses also.

I definitely agree that the GAs made this change knowing that it might reduce the number of full-time missionaries in the short term (by cutting down on the number of misses) but they’re also expecting that prospective missionaries will become more serious, which will make for a more dedicated, and just as large, missionary force in the long term. In terms of my figures, this would mean the whole point cloud is shifted up and to the right, as more candidates exceed both the screening cutoff and the actual performance cutoff.

The effect of raising the bar is to decrease misses while increasing false alarms.

That is always the case of raising a standard … though explaining it is probably a good thing rather than starting with it as a fact or just linking to an explanation.

What is interesting in this kind of standard is that the results are malleable. If I don’t reach the bar I can alter my approach and preparation and then reach it and a willingness to make a second effort to qualify is the sort of thing that also makes one a good missionary.

I’ve also known of people in alternate assignments, have one in my ward, and it seems a good thing, as it allows those who want to serve to be able to serve.

In my mission we had at least 6 sisters while I was out who should have stayed at home due to mental health issues but went home early

Wow. In my mission, the sisters generally seemed better prepared and better missionaries. Living in the mission field, the sisters I have met have followed that pattern for the most part. I guess experiences vary.

Vada, I have to note that people often judge others. I’ve had people decide I must have been unworthy because I’m short and I had a friend who was transferred out of our mission to a warmer one because of health issues. I was pleased as I could be to have a missionary return to a ward I was assigned to and bear his testimony, talk about his mission and then talk about how the most inspiring thing he had done was serve under Elder Adkins who was the best missionary he had ever met. So much for the assumptions some had about the transfer.

Eric, it is sad that a (Utah) culture of young men that believed you could sleep around as much as you wanted beforehand and still go is still there. We were talking about the Iron Rod and the mother of harlots today in gospel doctrine. Your comments bring that to mind.

My brother’s ward and the mission president he interacted with there about missionaries who were not physically capable of doing the walking or getting buy on only nine hours of sleep a day, was an eye opener for me. His area had gotten a lot of borderline missionaries and the effect was of my nephew’s graduating class, he is the only one planning on going on a mission.

There is a real cost to having people who are not really interested or prepared in regards to serving a mission.

I think the cost depends on who you are. If you are the false alarm in question, not being able to serve could well be devestating (maybe you think it shouldn’t be devestating, but these are just kids). If you are the companion of the miss, that might mess with your missionary game for a month or so. If you are the miss, you might really benefit from serving, no matter how poor your performance (or might not).

I served with an elder who was a miss. He messed with some companions and permanently affected an investigator and family. He went home excommunicated and I have no idea what happened to him. I really can’t imagine a worse missionary, yet it didn’t really affect too many other people.

Being a false alarm would be a bigger deal for a boy than a girl, as people don’t really care if a girl serves or not. I could easily imagine a boy, though, having a hard time getting married if he had not served.

I suspect the bar has changed for sisters, too. My sister who is currently serving was asked in EVERY interview if there was someone special in her life for whom she should not serve. I was not asked that 10 years ago. It would have angered me–can’t a boy wait as well as a girl?

If you are the companion of the miss, that might mess with your missionary game for a month or so.

How about an entire mission? If we applied current standards to my 12 companions, I think maybe 3 would have gone.

As for sisters – I think there has been local discouragement of sisters for decades. I don’t think it’s a new thing.

Thanks for the link to the original post, Ziff. I didn’t read all the comments, but I’m glad others realize the need to take away the social stigma associated with not serving a mission if we’re going to exempt many nice young men from serving.

I think I’m particularly sensitive to this right now because of my son’s autism diagnosis. While some parents haven’t wanted their children diagnosed in the past because of social stigma, this really isn’t an issue any more. An official diagnosis just helps him qualify for more services that help him function better. The only negative I’ve come across is that anyone with an autism diagnosis is excluded from serving a mission, no matter their worthiness, preparation, functional level, etc. I worry about how this will affect my son. His dad, his grandpas, his uncles, his cousins, his brothers have all served (or will serve) missions. He’ll be taught in primary his whole life that he should want to go on a mission, and that it’s something he should work for and do, but no matter how much he works he won’t be able to. Of course, since he just turned 3, I probably shouldn’t worry about this yet — there are still many years to go before it’s an issue, and who knows what will change in the mean time.

Vada –

One of my mission companions was autistic, and I had a nephew who was autistic. I’m not trained enough to know different levels, but I know my nephew wasn’t very high-functioning and wouldn’t have been able to serve, now or in the past. My mission companion was functioning enough to have gone to college and did OK. He was a good elder and tried his best, but there were issues.

I *so* agree that we need to remove the stigma for not serving full-time, but I think we need to continue to find ways for those members to serve part-time service missions.

One recent case in our ward is a young man who has some sort of mental/social impediment. I don’t know the details. He’s working in a storehouse capacity a couple of days a week, for what I think is 12 to 18 months. For him, it’s a wonderful opportunity. When they announced the call in church and had him stand, his parents were incredibly proud. His mom doesn’t often attend, but she was there that day, beaming. His dad was weeping with joy. It was an extremely touching moment.

In another case I know where the young man was unable to serve, he served as a ward missionary for 2 years, working closely with the full-time missionaries. We changed ward mission leaders a couple of times, but he was the constant.

I’m a big fan of service missions. There are a lot of older couples whose health or finances won’t allow them to serve a full-time couples mission, but who can spend 2 days a week working in the mission office or the storehouse or the cannery or the temple.

As far as the marriage stigma goes, I can’t think that it would really hurt a young man to say, when asked if he served a mission to say, “I wasn’t able to serve a full-time mission, but I had the blessing of serving a service mission.”

I think bishops need to be open to exploring those alternative possibilities. Once it’s identified that a full-time mission is not in the cards (for whatever reason, physical, mental, or worthiness-related), service mission opportunities should be identified. The bishops I know personally seem to be doing this aggressively. I hope the trend continues.

Yes, the bar was raised for sisters as well. My daughter has a physical problem that we thought might have prevented her from serving, would certainly prohibit her from serving outside the US or Canada. It did indeed raise questions at church headquarters, and they asked for more details from her physical therapist, etc.

She ended up going to South America, and having her mission extended to serve a few weeks longer than usual. It had a huge impact on her life/career and her employer is sending her back to that country in a few months.

I’m not so sure about “nobody caring” if women serve or not. I’ve met quite a few men who want to marry a returned missionary, some who waited for their wife to serve. President Benson and Elder Scott have both spoken/written about how their wife’s pre-marriage mission was such a great experience. In my stake, most young women serve, unless they happen to marry first.

10. “I served with an elder who was a miss. He messed with some companions and permanently affected an investigator and family. He went home excommunicated and I have no idea what happened to him. I really can’t imagine a worse missionary, yet it didn’t really affect too many other people.”

But didn’t that have a dramatic negative effect on the “investigator and family” and on the problem missionary himself? Isn’t that enough to support the wisdom of “raising the bar” so that he wouldn’t have had that impact? In my view, he adversely affected “too many people.”

(Naismith – I married a sister who served and was open when I was single about how RMs make better wives. Our daughter wants to serve and we are encouraging her. But I do think local stakes and wards, as a rule, don’t care if a woman serves. Maybe we need to move to your stake.)

Vada,

my son has ASD too but I haven’t worried about him serving- I know an autistic adult who served about 10 years ago, and some ASD kids and teens who are preparing. I assumed it was possible as long as the individual case seems workable, and sure, maybe it would be limited to the US, or maybe some non-proselytizing opportunity, but still, 2 years of service he can honestly refer to as “my mission”… for sure!

or at least, that’s what we’re going with.

A spectator, regarding the costs depending on who you are, that is definitely true. I was figuring that the Church was trying to think of aggregated costs across everyone, and to set the cutoff for missionary service so as to minimize those aggregate costs. But of course as you point out, the costs for individuals are going to vary widely depending on where they are relative to the cutoff to serve and how well they serve as missionaries.

Vada, I’m sorry that you have to worry about your son being stigmatized for (possibly?) not serving a full-time mission. I agree with you and queuno that, given how many non-worthiness related reasons people may have for not going, the stigma associated with not going should really be reduced.

Queuno, you said, “If we applied current standards to my 12 companions, I think maybe 3 would have gone.” Wow! That seems like a lot. Were their issues generally with worthiness or willingness to work (or both, or something else)?

cchrissyy,

There was a discussion about this recently on the LDSAutism yahoo group. My understanding is that even though it’s been decided on a case-by-case basis in the past, the current policy is that no one with a diagnosis of autism will be called on a proselyting mission. I think they might still be eligible for a full-time service mission, but I’m not sure. And since the policy has already changed, there’s nothing to say it wouldn’t change back (or change yet again in another way), which is why I probably shouldn’t be worrying about it yet. But I want to be aware of the policy, since I don’t want to set up hopes and plans for my son that he won’t be able to fulfill, through no fault of his own.

I’m de-lurking to chime in my agreement with the comments people have made about removing the stigma about guys who have chosen to not serve a mission. My brother is a full time student at BYU and he is somewhat of an *outcast* because he is 22 and has not and probably will not serve. People have automatically assumed the worst for the reason why. If they would take the time to ask, they would learn that the week my brother was preparing his papers (he had already had his interview with the bishop and had set the appointment with the stake president), our father suffered a fatal stroke. My brother chose to not turn in his papers in order to assist me with keeping our mother from completely losing it. He knew that we would support him if he did go, but I won’t lie, I was glad that he stayed home, because I would not have been able to take care of my mother by myself. I just find it more than irritating and unfair. OK, rant over. Back to lurking.

JrL–absolutely, it is subjective for me to judge that the affect had been born by “not too many people.” The people my heart went out to was the investigator yet I assume she was a willing participant (elder impregnated her). Of course, the elder, having greater knowledge, is more to blame. I really have no idea how the investigator felt about this. Maybe she was overjoyed; maybe they got married–I don’t know. But I assume she chose to involve herself in such a way. Anyway, it is a hard call to know where to draw the line, but all the people who would have been adversely affected (aside from unborn child at that point) would have chosen their degree of affiliation. Even companions who obviously should have reported on this guy way way before things went really wrong.

Queno–I have 2 brothers to have served and 3 sisters and myself. Among the girls, we just have not had problem companions (or been problem companions). But my brothers seem to have had many of them. It is my impression that some elders get tagged as capable of wrangling problem companions and are therefore assigned a string of them. Perhaps you, like my brothers, fit this category?

I had a companion on my mission who had a mental disability. My first hint that something was up was when the Mission President took me aside the zone conference before transfers and actually forewarned me. His maturity level was about that of a 14 year old though he was actually around 30, his confidence level was very low. I had to threaten to tickle him to get him to study, he regularly locked himself in the bathroom for hours at a time to avoid proselyting, he never contributed to a discussion and he only did 2 door approaches the entire time. I announced to him at most every door that I was going to let him do this one and it was his lucky day. I would say it didn’t work, but it turned out that 2 door approaches was 2 more than he had done in over a year on his mission to that point. Our pool of investigators shrank, temporarily.

So why do I share this happy story, because this companion taught me more about myself than any companion on my mission. I love that Elder, I really do. This experience strengthened my relationship with God like no refiner’s fire could. It shaped who I am and what I have done with my life. I am not so sure raising the bar is necessarily a good thing in the case of disability or medical conditions. I worry about our own underestimations and prejudices.

I thought for a moment you must be in my ward, except his Dad is my bishop and his mom attends all the time.

from my perspective as a doctor – I have seen several elders and sisters who had to come home early (a couple of sisters who were only out a month or less) due to “mental breakdowns”. As I was the personal doctor to one of these sisters, I can vouch for the fact that if she had been willing to take her medications as prescribed and advised, she probably would have been able to have a successful mission. However, she went against medical advice, and came home a month into her mission, due to stress over a change in her companionship. I have also treated several actively serving full time missionaries for mental disorders over the past year at the request of the mission president, and when they were compliant with their treatment regimes, they were able to stay out on the mission, improve the quality of their service, and complete happy and successful missions. Bottom line – some (not all) of mental health conditions are treatable enough to allow those suffering from them to be successful in a mission, if they get appropriate treatment and stick to the treatment plan.

On the other side, my bishop served a very successful mission in Thailand and is now a successful bishop – he admits he had a moral failing prior to his mission that would have prevented him from serving under the “Raise the Bar” standards – cost/benefit?