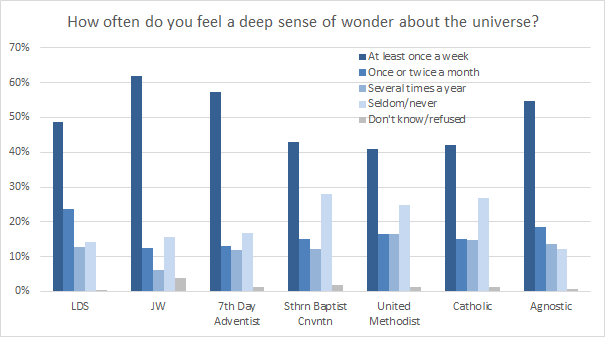

Earlier this year, I blogged about the Pew Religious Landscape Study and looked at some of the results, comparing Mormons to members of a few other groups. One of the questions in the survey asked people how often they felt a deep sense of wonder about the universe. Here are results for Mormons and the other groups I was looking at.

Mormons don’t have quite as many people answering “at least once a week” as do Jehovah’s Witnesses, Seventh Day Adventists, or agnostics, but like all the groups I looked at, we have more people answering this than any other response frequency. By this measure, Mormons are pretty middle-of-the-pack when it comes to experiencing wonder.

I was recently thinking about this question when I read Nate Staniforth’s book Here Is Real Magic. Staniforth is a magician, and the book is largely memoir, but he also spends a fair amount of time discussing the question of why magic is fascinating to him. The answer boils down to wonder: Performing magic often allows him to see wonder provoked in his audiences, and he treasures this experience because in his view, wonder is so uncommon and so precious. He even subtitles the book A Magician’s Search for Wonder in the Modern World. Here’s one point where he describes his experience of using magic to induce wonder:

From the students on the playground at recess to this man named Ahmed who worked in a terrible neighborhood in Kolkata, the response to great magic is the same: a mouth stunned open, widening eyes, fear, doubt, and then openly, nakedly, joy. Pure joy. The transformation is far, far more amazing than the trick, which is just a tool designed to create this moment. A moment of pure astonishment makes you forget to be cool. It makes you forget to be composed or distinguished. It make you forget to–consciously–be anything. The faces that are revealed when our masks of self-awareness are propriety are blasted away are, simply, beautiful [p. 100].