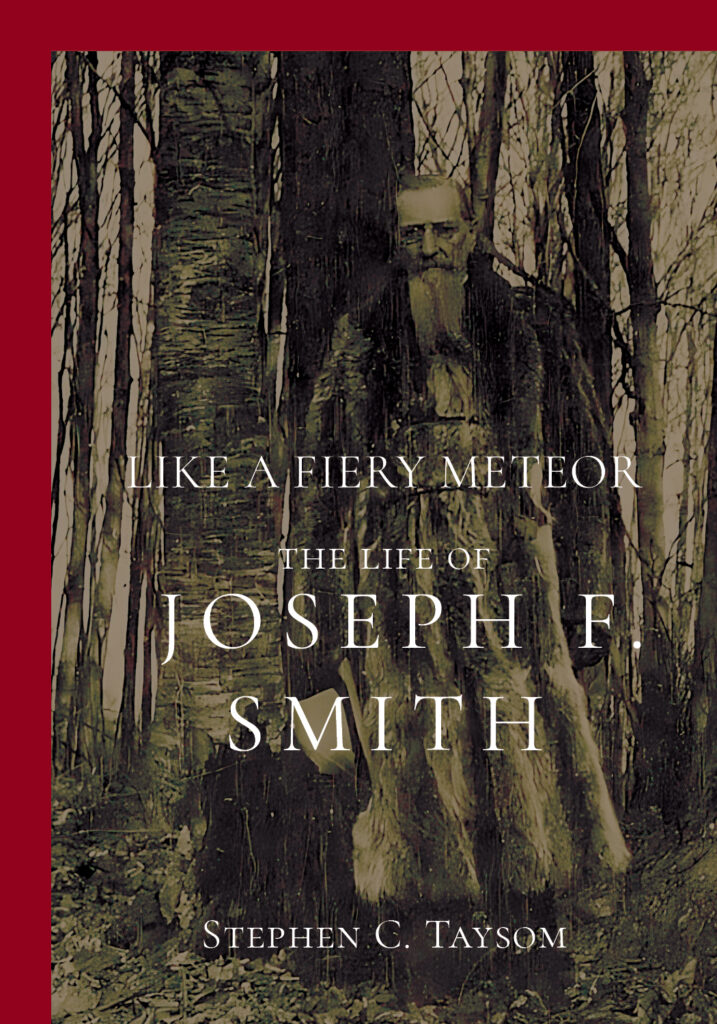

I recently read Stephen C. Taysom’s biography of Joseph F. Smith, Like a Fiery Meteor. I’m acquainted with the author, so I’m going to refer to him as Steve, because it would sound strange to my ear to call him Taysom. Also, I’m going to follow his convention of referring to Joseph F. Smith as JFS.

- I appreciate that Steve takes his readers seriously enough to occasionally introduce a theoretical framework for understanding an event in JFS’s life. For example, when talking about the Mormon diaspora that followed the deaths of Joseph and Hyrum, he first briefly discusses diasporas in general and the idea of returning to a homeland, and then shows how Mormons were both thinking of returning to a particular place, and also to an imagined one, an idealized version of the United States. Or again, when talking about how JFS made sense of the Manifesto, both for himself and for Mormons in general, Steve first refers to a historian who’s thought about meaning-making in Judeo-Christian religions more generally, before getting into applying the historian’s ideas to the particular situation JFS was in.

- Steve is very evenhanded and clear-eyed in talking about things JFS did. He doesn’t shy away from explaining incidents like where JFS threatened (and maybe attacked) a school teacher, or when he abused his first wife or when he severely beat his neighbor. But he also shows over and over how tenderhearted JFS was in concern for his family, his many children especially, and his grief when a shockingly large number of them died young.

- He gets down in the details a lot with quotes from JFS’s letters and journals. I found these so interesting, as I felt like Steve deployed them so well to show what issues were concerning JFS at particular times. Especially interesting is when he’d find that JFS had misremembered events, and how telling the way he misremembered things often was.

- Related to the previous point, he really shows how some issues were just chronically on JFS’s mind, and really built into his worldview, for the whole of his life. For example, JFS seemed to be always on guard against the threat of outsiders, and had a very us-against-them view. I don’t recall the exact spot, but Steve quotes him once referring to “the mob” who was after Hyrum and Joseph, and it was clear that it wasn’t a particular mob, but just the generalized bad people of the world, who were forever at war with the Church.

- I found it fascinating to read of so many details of missions that were clearly dramatically different from the ones I’m familiar with. For example, JFS found some peace near the end of his first mission to Hawaii doing farm work at an LDS settlement, with only a little preaching on the side. Or decades later, when he was a mission president in England, he had trouble with his missionaries falling in love with the women there.

- I was frankly amazed to learn how JFS saw himself as an outsider in the Church and in leadership for much of his life. But Steve explains well how this came to be, how Brigham Young didn’t like either Emma or Lucy Mack Smith, and with Hyrum having been killed too, and many of the Smiths staying in the Midwest to eventually join the RLDS, JFS and his family were no longer central to the Church. And Steve makes the case that Brigham was motivated to call JFS both as an apostle and into the First Presidency largely as a response to the threat of RLDS missionaries coming to Utah.

- I have read little about the immediate context of the issuing of the Manifesto, so I was fascinated to read how GAs including JFS were pronouncing that plural marriage was essential into the 1880s. It seems like it was only in the year or two prior to 1890 that they appear to have imagined that they might have to back down on it, and they began doing things like advising men that maybe now wasn’t the best time to take another wife. But then mixed messaging, and clearly semi-stealthy authorization of more plural marriages, continued for so long. As Steve puts it, “The Manifesto, and the subsequent scaling back of plural marriage, had certainly achieved the desired end when Utah attained its statehood in 1896, but it remained for JFS to decide if the church really meant it.”

- Related to the issue of the end (or at least reduction) in polygamy, I liked the point Steve makes several times that the Church (and JFS when he was president) had to change while explaining that it wasn’t really changing. I thought this was a great summary: “Successful religions, meaning those that are historically persistent, find ways to make necessary changes to remain viable within a given cultural and historical context while simultaneously explaining away the changes as nonexistent, unimportant, or as epiphenomena that are changes in appearance only, and which are actually in service of a larger, unchanging phenomenon.”

- Steve points out in several places that JFS was the author of many changes that put the LDS Church on the path to being what it is today. He was clearly very interested in regularizing and standardizing belief and practice, and it’s clear that that impulse was carried on through his son Joseph Fielding Smith (and of course, Bruce R. McConkie). He was also prudish about sex, which Steve points out while quoting a letter that sounds like it’s JFS worrying about masturbation, but he can’t bring himself to even say words adjacent to it. All the GAs today who say things like “sacred power of procreation” are clearly following in his footsteps. Also, although I didn’t notice Steve crediting JFS as the originator of the phrase, he clearly had a fondness for saying “Obedience is the first law of heaven,” so he seems likely to have been its first popularizer.

- I found Steve’s discussion of JFS’s revelation of people in the afterlife, now found in D&C 138, seriously beautiful. He describes it so perfectly as the end point of a lifetime of JFS’s concern over his family, so many of whom died before their time. It was an excellent piece of writing to cap the story.

It’s not a short book, but I found it to be so, so worth it. It was so good that I would have happily read it at twice the length. And really, I’m limiting myself and combining points to limit myself to only ten things I love. If you’re interested in Mormon history, I recommend you give Like a Fiery Meteor a shot!

“Steve takes his readers seriously” is probably the best compliment I could get. Thank you.

You’re welcome! Thanks so much for writing such a great book! I really did appreciate that you took readers seriously enough to figure that you could introduce theoretical frameworks to help us understand how better to think about particular incidents in JFS’s life.

Thank you Ziff for the great review and, thank you Steve for the great work in writing the book. I will read it soon!