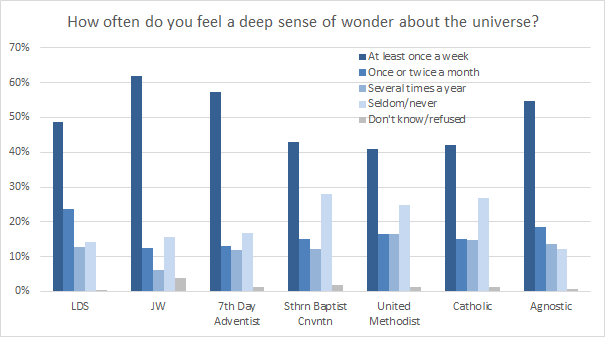

Earlier this year, I blogged about the Pew Religious Landscape Study and looked at some of the results, comparing Mormons to members of a few other groups. One of the questions in the survey asked people how often they felt a deep sense of wonder about the universe. Here are results for Mormons and the other groups I was looking at.

Mormons don’t have quite as many people answering “at least once a week” as do Jehovah’s Witnesses, Seventh Day Adventists, or agnostics, but like all the groups I looked at, we have more people answering this than any other response frequency. By this measure, Mormons are pretty middle-of-the-pack when it comes to experiencing wonder.

I was recently thinking about this question when I read Nate Staniforth’s book Here Is Real Magic. Staniforth is a magician, and the book is largely memoir, but he also spends a fair amount of time discussing the question of why magic is fascinating to him. The answer boils down to wonder: Performing magic often allows him to see wonder provoked in his audiences, and he treasures this experience because in his view, wonder is so uncommon and so precious. He even subtitles the book A Magician’s Search for Wonder in the Modern World. Here’s one point where he describes his experience of using magic to induce wonder:

From the students on the playground at recess to this man named Ahmed who worked in a terrible neighborhood in Kolkata, the response to great magic is the same: a mouth stunned open, widening eyes, fear, doubt, and then openly, nakedly, joy. Pure joy. The transformation is far, far more amazing than the trick, which is just a tool designed to create this moment. A moment of pure astonishment makes you forget to be cool. It makes you forget to be composed or distinguished. It make you forget to–consciously–be anything. The faces that are revealed when our masks of self-awareness are propriety are blasted away are, simply, beautiful [p. 100].

I think what was so striking to me about Staniforth’s discussion of wonder is that my experience falls much more in line with his view that wonder is rare than it does with the Pew results where, across religious traditions or lack of religious tradition, most people report feeling a deep sense of wonder once a week or more. I feel like, particularly as I’ve aged (and I am currently middle aged), wonder is very difficult for me to find. My life is dominated by the mundane, by the routine. I can look backward and forward and see an endless string of days in either direction that all look pretty much the same. I’m busy doing pretty much the same things over and over and over. And wonder has a hard time fitting in all that crushing routine.

I feel like wonder might be kind of a vague term here, and I might be defining it differently from how the Pew respondents define it. I’m thinking of wonder as a feeling provoked by having my notions of how the world is put together and how its pieces relate to one another upset, even slightly, in a way that suggests greater possibility than I had previously imagined. Here’s a related bit from Staniforth where he describes how he thinks people would react to his magic if they thought it were real:

The appropriate response to something that feels truly impossible is not applause: the appropriate response is fear; fear and, as you are running away, some hidden, pure, secret joy that maybe the world is bigger than you thought [p. 17].

Maybe the world is bigger than I thought. That’s what I’m hoping wonder to push me to see. Religion should be an ideal vehicle for bringing people to wonder, what with its discussion of grand ideas of right and wrong and truth and falsehood, not to mention god(s) and afterlife(lives). But Staniforth has this thought-provoking line that made me wonder whether Mormonism might be particularly inhospitable to wonder as religions go:

I worry that the experience of wonder becomes harder and harder for me to find as I get older. This has nothing to do with education–wonder is not the product of ignorance–but it does have something to do with certainty [p. 14].

Mormonism is perhaps in love with nothing so much as certainty. We know where we came from, why we’re here, and where we’re going. We know things beyond a shadow of a doubt, with every fiber of our being. We have the entire afterlife worked out (well, maybe) with careful delineations about who will end up where, and what they’ll be doing. We have no room for uncertainty. You know or you go home. As Yoda might put it if he had been a Mormon prophet, “Know or know not. There is no believe.”

I realize that the Pew data totally don’t back me up on this, but I do think that it’s at least possible that the Church isn’t an easy place to experience wonder because we’re so certain of so many things. Truthfully, for myself, I’ve turned my search for wonder mostly to novels and movies, where I love the occasional unexpected experience of having my worldview upended, or even just jostled a little. And there are still bits of religion that can do the same thing. For example, here’s one of my favorite scriptures:

But as it is written, Eye hath not seen, nor ear heard, neither have entered into the heart of man, the things which God hath prepared for them that love him [1 Cor 2:9].

I just love the idea that there’s still mystery, that there are still unknowns in what might be.

***********

Anyway, having said all this, I realize that I’m probably falling prey to one of my favorite errors: overgeneralizing from my own experience. It seems very likely that there’s lots of variation in how people experience wonder, and how frequently they do, and how they describe it, and how they think about it, and whether certainty has anything to do with it as I think it is. And the connection to Mormonism is pretty tenuous, I concede, especially given the Pew data. But what I’d really like to hear is how you think about and experience wonder, and how it connects (if it does) to your religious belief or experience.

Now that I am not so orthodox, I look for manifestations of divinity that cause me to experience wonder, mostly through nature or literature as I consider what lead to its creation. I also experience wonder when I read or hear accounts of extraordinary acts of forgiveness.

Wonder gives me hope that there is more to discover and that I have potential to experience new things.

My mother said this was part of the joy of being a parent. You may be older, but you are surrounded by people who are experiencing things for the first time, and you get to share things and see the wonder again through their eyes. I agree. At this point I have trouble motivating myself to do cool, full of wonder types of things for myself, but I am motivated to find somewhere without light pollution while on a long drive (we live in Seattle) in order for my children to see the stars because I remember I saw them when I was a kid. So I get to remind myself, relive things, etc. because I am a parent.

I wonder why we don’t experience more wonder.