I first read Mother’s Milk, by Rachel Hunt Steenblik, last July, about a month after I learned I was pregnant for the first time. I tried to see myself as the mother portrayed in these poems, but mostly failed: I had constant nausea and threw up 5-10 time a day for two months straight in my first trimester, and so I felt no magical love connection to the fetus, whom we nicknamed Barfolomew. I mostly just felt tired, and irritated at the way this hostile force had overtaken my body. The poems were lovely, tasty snack-sized deep thoughts, but, like Lynnette has written about on this blog, I wasn’t really a Heavenly Mother person, and the mothering portrayed in many of the poems–nursing, weaning, comforting in the night–didn’t resonate with me. I tried to hold space to change my mind, though: many of my friends talked about childbirth as a quasi-magical experience, a primal connection to their mothering self, and, despite the pain, glowed about the love they felt for their child right away, or for a rush of instant recognition when their child was placed on their chest.

For me? Not so much. After 31 hours in labor, 4 hours of pushing, plus some emergency interventions, all I felt was exhaustion. I remember looking at the baby and thinking, distinctly, that I didn’t recognize him, and there was no rush of instant love. He wasn’t Barfolomew, somehow, but I didn’t know who he was instead, and his features weren’t immediately identifiable as mine or my husband’s. He was a mysterious new person, and suddenly my responsibility, and I was tired already. The nurse pushed me to breastfeed as my son rooted around, and I begged to take a nap instead.

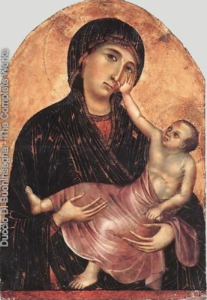

Those typical experiences aren’t necessary to good mothering, of course, and as my son grows and develops–he can smile now!–I like him more and more. Still, giving birth didn’t convert me to gender essentialist expectations of motherhood and the supposed immediate passionate bond between mother and child, and while the hormone rush of breastfeeding helped, as my son and I form a mother-and-child tableau through hours of feeding and snuggling, sometimes we’re a Renaissance painting, with a peaceful gold halo, and sometimes we’re one of those late 13th century paintings in which Jesus looks like any other hungry baby and the Virgin Mary’s face looks for someone to save her from this furious child savaging her nipples.

So back to the poems: re-reading them now for this review, as my 8 week old naps, I still skim over some of them that don’t resonate with me, focused as they are on the image of the Mother as a “nursing Queen.” Those poems don’t match my experiences, at least not yet, and so they don’t make me long for a Heavenly Mother figure where the physical aspects of mothering a small child are the primary metaphor. I don’t hate those poems, certainly; they’re clearly deeply personal to Steenblik, a mother of young children herself, and thus they don’t anger me like so much of the romanticized Heavenly Mother rhetoric produced by older men. They’re just not really my thing. If they were the whole, or even the bulk, of the collection I’d find it sweet, but not for me, and move on.

But, luckily for me, I can’t quite move on so simply: the simple existence of this poetry collection is another small step forward for Mormonism, merely by reducing the taboo around exploring the idea of Heavenly Mother, but Steenblik’s real achievement with this collection is the expansion of the notion of Heavenly Mother beyond the titular metaphor. (Titular! Ha!) All the poems are intimate and personal, but not all of them present Heavenly Mother as a mother, necessarily, but as a creator:

What the Mother Taught Me

Creation is

more than

procreation.

It is snow, birds,

trees, moon,

and song.

She’s a divine being in Her own right, and tries on personae beyond the caretaker:

The Author

When Her children sleep,

She writes.

Moreover, in pondering the divine feminine, Steenblik acknowledges the earthly feminine, too; in a recurring motif throughout the poems, she acknowledges what she’s learned about Heavenly Mother from prominent writers, thinkers, and friends, many of them women cited only by first name (Rosemary, Margaret, Janice, Carol, Janan, Joanna), in a tender sisterhood of spiritual insights.

What Joanna Taught Me

God is a Mother and

a Father.

I matter. I matter.

I matter.

Too often as a church our vision of Heavenly Mother is through a glass darkly: if She exists, we don’t talk about Her enough, and when we do, it’s in narrow terms, projecting our contemporary American feminine stereotypes onto Her, too often turning Her into a kind of divine Fascinating Woman, making sure to dress in skirts so that men will help Her, and, presumably, complimenting Her spouse on His manly skills, like sawing logs or taming horses. Steenblik’s poems avoid these crude stereotypes while still depicting her as distinctly feminine, a potential divine role model for women, even acknowledging explicitly that mothering can’t be the ultimate and only extent of a woman’s contributions:

The Mother Understands

The divine

Mother

of us all,

understands

not every

woman

is a mother.

These poems are lovely, and important, and they succeed on their own terms, prompting thought and reflection from the reader. I’m not yet a Heavenly Mother seeker, personally, and admit to retaining some skepticism about Her, but this collection made me at least *want* to seek her, a first. Most of all, they made me hungry for more: if She exists, and if gender really is eternal, we need more talk of Heavenly Mother beyond the pedestal, and especially more broad visions of what She could be. This collection should be a gauntlet thrown down to other aspiring poets out there: who is Heavenly Mother to you? Who have you learned from? What are the farthest reaches of what a divine feminine could be? Tell us. In five years–or ten, or twenty–I’d love to see a Mormon press not only be able to publish a full anthology of writing about Heavenly Mother–poems but also essays and fiction and scholarship seeking Her–and genuinely struggle to narrow down the wealth of material.

To that end, I offer my own weak imitation of Steenblik’s style:

What Duccio Taught Me

Sometimes a God weeps

And a Mother is tired.

She loves me,

And holds me,

But her eyes beg for a break.

I love your review, Petra, and your points about discussion of Heavenly Mother. A divine Fascinating Womanhood is, unfortunately, a spot on description of how she seems to be imagined in the Church.

Not related to the book review, but I absolutely understand not feeling that “instant love.” With my oldest I remember trying to conjure up that feeling and by 8 weeks, I had a short-lived flight/instant of that feeling while taking a walk one day. It definitely grew on me. I put myself into the breastfeeding because I know that that’s what their brains expect to be receiving nutrient-wise evolutionarily. Also babywearing and all that. But it wasn’t from some maternal love that sprang from me. Even in pregnancy I didn’t feel like a “baby” was there until 13, or 20 weeks with one. Like I could have had a miscarriage up to those points and not have felt like I lost a baby, but just a chance to have a baby eventually.

Anyway, that’s a digression. I haven’t read this book yet (I’m a slacker) but I do plan on it.

I was surprised by how much I liked this book–I’ve also never felt like a “Heavenly Mother” person, and though I have kids, I rarely feel glowy/lovey/mothery (I’m more of a “sit on the couch and read a book while my children amuse themselves” mother). Plus my own relationship with my mother is complicated and I’ve yet to experience any sort of warm, nurturing mother love in my life. But, I thought this book was beautiful and it helped me understand more about those who do want to know more about Heavenly Mother. I loved most of the poems, and I really loved the footnotes too. I’ve also been surprised by how well it’s been received by a number of my friends who I thought might like it for all different reasons (poetry/feminism/HM/cheesiness).